Data protection by design and by default (DPbDD) is how organisations put the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)’s rules and principles into practice.

But the GDPR dedicates just one of its 99 articles to DPbDD—a concept that involves embedding privacy into product design, ensuring people can exercise data protection rights, implementing technical controls to keep data secure, and more.

Below we’ll explain what DPbDD is, break down what the GDPR says about it, and explore DPbDD guidance and enforcement from EU regulators.

What Is Data Protection by Design and By Default?

DPbDD is at the core of GDPR compliance. The concept is split into two interrelated parts:

- Data protection by design: Embedding data protection into the core of systems, processes and products. For example:

- A social app collects only a person’s email address for login purposes and requires the user to choose a strong password and set up multi-factor authentication.

- Data protection by default: Enabling the highest data protection standards automatically. For example:

- A fitness app keeps exercise logs private by default but allows users to make their results public if they wish.

Organisations implement DPbDD via “technical and organisational measures” – technology, processes, and practices that make data protection real.

Many GDPR enforcement cases involve companies that failed to get DPbDD right.

Example: The Croatian regulator fined a betting company €380,000, in part due to a violation of data protection by design. The company collected both sides of customers’ credit cards and failed to apply technical measures to keep the details secure.

Privacy By Design

The GDPR introduced the concept of data protection by design and default into EU law. However, the concept originates with “privacy by design”, developed in 1995 by Ontario’s then Information and Privacy Commissioner, Ann Cavoukian.

In January 2023, the International Standards Organization (ISO) also adopted a new framework: “ISO 31700 — Privacy by design for consumer goods and services”.

“Privacy by design” and “data protection by design and by default” are similar concepts.

But although the GDPR explains DPbDD in just three paragraphs, the doctrine is somewhat broader than privacy by design. For example, the GDPR requires you to consider more than just privacy risks — you need to consider any risks to people’s “rights and freedoms”.

Example: Under the GDPR, people have the right to access their personal data. The Hungarian regulator fined Deichmann for failing to fulfil requests for access to CCTV footage. The regulator said the company’s systems were not designed to facilitate the right of access.

What Does the GDPR Say About Data Protection by Design and By Default?

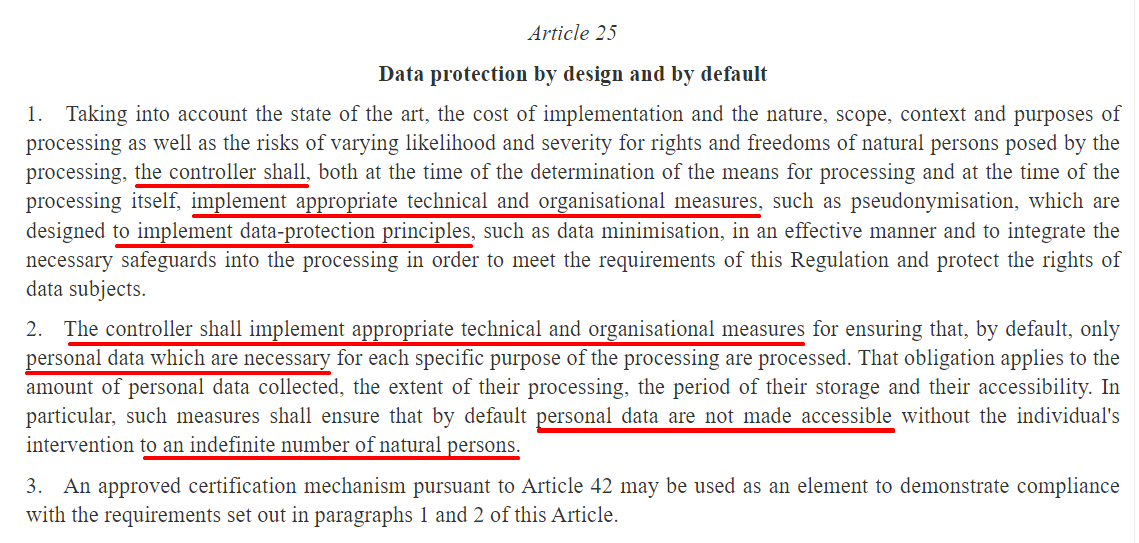

The best source of information about DPbDD is Article 25 of the GDPR. Here’s the full article:

Now we’ll break down each element of Article 25 to determine what the GDPR means by “data protection by design and by default”. We’ll highlight some terms that might be unfamiliar and explain them below.

Article 25 (1): Data Protection by Design

Both before and during the processing of personal data, the controller must implement technical and organisational measures such as pseudonymisation.

These measures must be designed to:

- Implement data protection principles, such as data minimisation.

- Integrate the necessary safeguards to:

- Achieve GDPR compliance, and

- Protect data subject rights.

When implementing these measures, controllers should take the following factors into account:

- The “state of the art”.

- The cost of implementation.

- The nature, scope, context, and purpose of the processing.

- The risks, including:

- How likely it is that people’s rights and freedoms will be affected by the processing, and

- How severe any impact on people’s rights and freedoms would be.

Article 25 (2): Data Protection by Default

The controller must implement technical and organisational measures to ensure that by default, the controller only processes the personal data necessary for each specific processing purpose.

This obligation applies to:

- The amount of personal data collected.

- The extent of the processing.

- How long the personal data is stored.

- Who can access the personal data.

By default, personal data should not be made accessible to an “indefinite number” of people unless the data subject intentionally permits this.

Definitions

We highlighted a few terms above that might need further explanation:

- Controller: A person or organisation that “determines the purposes and means” of processing personal data. For example: A company decides to run to increase growth by running an email marketing campaign. The company is the controller of any personal data processed for this purpose. The company hires a marketing agency to run the campaign on its behalf. The agency is not a controller—it’s a “processor”.

- Data protection principles: Seven principles set out at Article 5 of the GDPR that underpin the processing of personal data. In the context of DPbDD, the principle of “data minimisation” is particularly important: You must only process the personal data necessary for a specified purpose.

- Data subject rights: A data subject is a natural person (living individual) to whom personal data relates. Data subjects have several rights under the GDPR, including the rights to access, correct, or delete their personal data.

- Pseudonymisation: Replacing identifiers (such as names, user IDs, or IP addresses) in a dataset with non-identifiers so that the identifiers can only be linked to an individual using additional information (i.e. a key) kept separately from the dataset.

- Risk to rights and freedoms: Any harm that could result from processing personal data, including discrimination, fraud, financial loss, reputational damage, intrusion on privacy, or loss of confidentiality.

- State of the art: The current state of technology and organisational practice.

Technical and Organisational Measures

On a practical level, DPbDD is about the “technical and organisational measures” that must be implemented by the controller. When using a processor, the controller may also need to ensure that the processor applies technical and organisational measures.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB), a body made up of data protection regulators from across the European Economic Area (EEA), gives some examples of the sorts of measures that can help achieve DPbDD:

- Pseudonymisation

- Privacy and information security management systems

- Malware detection systems

- Digitising personal data

- Enabling data subjects to intervene in the processing

- Providing information about the storage of personal data

- Training employees about “basic cyber hygiene”

- Requiring processors to implement data minimisation

Not all of these measures will be relevant to every data processing activity. The GDPR doesn’t specify which technical and organisational measures apply to a given situation.

What’s important is that technical and organisational measures must be “effective”. The EDPB says that “effectiveness is at the heart of the concept of data protection by design”.

Technical and organisational measures must achieve a given aim. Controllers must be able to check and demonstrate that their chosen measures have their intended effect.

Example: A data breach exposed 533 million Facebook users’ email addresses. Meta said it had implemented technical measures to prevent such a data breach. But the Irish regulator found that Meta had still violated “data protection by design” as the measures were ineffective.

Elements of Data Protection by Design and by Default

Article 25 of the GDPR requires controllers to take certain elements into account when considering technical and organisational measures.

The EDPB provides some guidance concerning each of these elements, such as how much the measures will cost and whether they will work given the context of the processing.

Here’s a brief summary of some of this part of the EDPB’s guidance:

- The “state of the art”: Keep up-to-date with technical developments that could put personal data at risk or help you improve data protection and security. Some mature privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) might represent state-of-the-art technology, but PETs alone don’t necessarily ensure compliance.

- Cost: You don’t need to spend a disproportionate amount of money on data protection. But if you can’t afford to implement effective data protection measures for a given processing activity, you shouldn’t undertake the activity at all.

- Nature, scope, context and purpose of the processing: When implementing technical and organisational measures, consider:

- The characteristics (nature) of the processing, including the types of data involved and the implications for data subjects.

- The size and range (scope) of the processing, including how much data is involved and how long the processing will take.

- The circumstances (context) of the processing, which might influence data subjects’ expectations.

- The aims (purpose) of the processing.

- Risks to data subjects’ rights and freedoms: Conduct a risk assessment to determine how different groups of data subjects (e.g. children) could be impacted by the processing. Consider whether you need to conduct a data protection impact assessment (DPIA). Identify and implement risk mitigation measures.

- Data minimisation by default: Ensure settings are configured to the most private option unless the user intervenes.

Example: A Finnish hospital district enabled location tracking on employee devices by default. Because this processing was not necessary or proportionate to the controller’s aims, the Finnish regulator found that a hospital district had failed to apply DPbDD.

Cases Involving Data Protection by Design and By Default

Throughout the article, we’ve provided brief examples of GDPR cases involving DPbDD. Because DPbDD covers so many areas of GDPR compliance, there are many such cases.

Here’s a detailed look at a further three GDPR enforcement decisions involving DPbDD.

Meta: Publishing Children’s Contact Details By Default

In September 2022, the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) imposed a €405 million fine on Meta for publishing children’s contact details on Instagram.

The issue was raised by a researcher who found that children were converting their Instagram accounts from personal to business accounts.

Using a business account, a user received additional analytics about engagement with their posts. However, the user’s phone number and email address became publicly available by default.

Following an intervention by the EDPB, the Irish DPC found that Meta had not applied DPbDD and had therefore violated Article 25 of the GDPR (among other provisions).

- Data protection by design: Meta failed to prevent children from converting their personal accounts to business accounts. Contact details were published in plain text on the open web and could be bulk-collected via “scraping” software.

- Data protection by default: Instagram business accounts published contact details by default, with an opt-out facility added after the investigation had begun.

On top of the €405 million fine, Meta was forced to redesign its systems in a more privacy-friendly way.

Excessive ID Checks for Subject Access Requests

In September 2022, the Spanish data protection authority, known as the “AEPD”, imposed a €300,000 fine on an employment agency for violating DPbDD when facilitating people’s access to personal data.

Under the GDPR, data subjects can request access to a copy of their personal data. A controller should take reasonable steps to verify the identity of the person making the request to ensure that they don’t breach the data subject’s confidentiality.

In this case, the controller requested the data subject’s ID. The AEPD found that the controller did not need to request any additional information to verify the request. Asking for ID was unnecessary as the request came via the data subject’s usual email address.

This case caused some controversy, as the principle of DPbDD requires the controller to mitigate risks such as identity theft. The controller argued that its process mitigated this risk by ensuring that personal data was not provided to the wrong person.

However, the GDPR also requires controllers to assess these risks alongside the nature, purpose, and context of the processing. The AEPD found that the controller had got the balance wrong — it had failed to design its systems to minimise the collection of personal data.

Choice of Microsoft as a Service Provider

In March 2023, the Finnish data protection authority found that a local government body had violated the “data protection by default” principle by using an inappropriate processor (service provider).

The local government body used Microsoft Office 365 to manage school administration. By default, the software revealed a lot of personal data about each child across all the city’s schools.

The Finnish regulator noted that it was not possible to make certain personal data private using Microsoft Office 365. As such, the local government body had failed to meet the GDPR’s DPbDD requirements by using Microsoft’s products.

Under the GDPR, a controller is generally responsible for the compliance of any processor operating on its behalf. This case shows how DPbDD is relevant when choosing an appropriate service provider.

Making GDPR Compliance Real Through Data Protection By Design and By Default

DPbDD ultimately means choosing technical and organisational measures that will help you meet the GDPR’s requirements. But this can be a complicated task that covers every aspect of your organisation’s data processing activities.

DPbDD is among the GDPR’s most important concepts as it requires organisations to put the law’s rules and principles into practice. Think carefully about how to embed privacy and data protection into your organisation, your services, and your products.

No Cookie Banners. Resilient against AdBlockers.

Try Wide Angle Analytics!