Thousands of companies rely on standard contractual clauses (SCCs) to transfer personal data out of the EU. But there is a lot of uncertainty about how SCCs work and whether they are effective.

This guide explores what SCCs are, how to use them, and when not to use them. We’ll also explain how the Schrems II judgment impacts SCCs, and provide a case study about using SCCs with Amazon Web Services (AWS).

What Are Standard Contractual Clauses?

Standard contractual clauses (SCCs) are a tool used to facilitate international data transfers under the GDPR.

SCCs are the European Commission’s “model clauses” that can form part of a contract between an EU-based organisation and a non-EU organisation.

The GDPR sets a high standard of data protection for people in the EU (plus the UK, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway—we’ll use “the EU” as shorthand). SCCs are designed to ensure that when personal data leaves the EU, it is still protected to EU standards.

SCCs are one of several possible methods for exporting personal data listed under Chapter V of the GDPR. As we’ll explore below, SCCs are not a “magic bullet” and do not automatically make a data transfer legal.

How Do Standard Contractual Clauses Work?

Here’s an example of how SCCs might be used.

A French clothing retailer collects personal data from someone in Germany. Because the French company is covered by the GDPR, it must follow all the law’s requirements for processing the German person’s data.

But the French clothing retailer wants to use an email marketing company based in Australia, which is a “third country” (non-EU country). The retailer will have to export its customer’s personal data to Australia, where data protection law is weaker than the EU’s.

The French and Australian companies can agree to a contract containing SCCs. The contract will require the Australian company to protect the personal data to EU standards. For example, by implementing security measures and assisting with data subject requests.

So far, so good.

But a contract is just “paperwork”. A contract does not override national law—with or without SCCs.

We’ll explain why this is a problem later in the article.

Standard Contractual Clauses Modules

There are four different “modules” of SCCs designed for different situations, depending on the role of the exporter and importer of the personal data:

- Controller to controller

- Controller to processor

- Processor to processor

- Processor to controller

The European Commission provides a Word document containing all SCCs. The document identified which SCCs are necessary for each “module”.

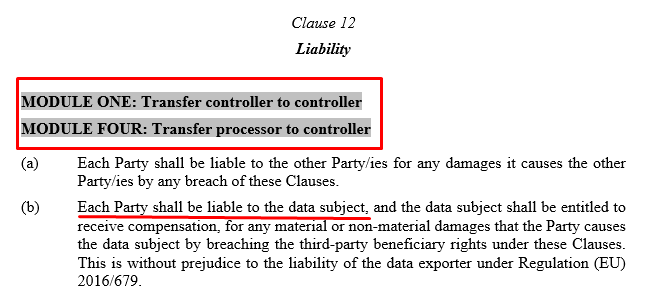

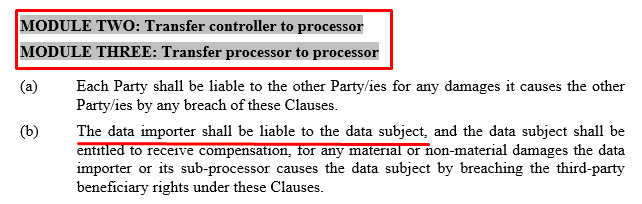

For example, there are two versions of Clause 12, which sets out the rules on liability.

The first version of Clause 12 is for modules one and four, where the third-country data importer is a controller. This version of the clause states that each party is liable to the data subject.

The second version of Clause 12 is for modules 2 and 3, where the third-country importer is a processor. In this version of Clause 12, only the data importer is liable to the data subject (with some exceptions).

Alternatives to Standard Contractual Clauses

SCCs are not the only method for making an international data transfer under the GDPR. Let’s look briefly at three of the alternatives.

Adequacy Decision

An international data transfer can proceed without SCCs if the data importer is in a jurisdiction covered by an “adequacy decision”.

Under the adequacy process, the Commission assesses a third country’s data protection and human rights stanards. If the third country provides “essentially equivalent” protection to data subjects as under EU law, the Commission can adopt an adequacy decision.

There are 14 adequate jurisdictions, including Andorra, New Zealand, and Japan. The US has received two adequacy decisions, both of which have been invalidated.

Binding Contractual Clauses

Binding contractual clauses (BCRs) can facilitate international data transfers between entities in an international corporate group, or a “group of undertakings”. Like SCCs, BCRs place legal obligations on data importers to process personal data to EU standards.

BCRs must be approved by a data protection authority (DPA). The BCR approval process is long and complicated. Since the GDPR took effect, fewer than 50 sets of BCRs have been approved (many of which apply to the same companies).

BCRs are sometimes called the “gold standard” of international data transfers. However, BCRs suffer a similar problem to SCCs—they cannot override national law.

Derogations for Specific Situations

International data transfers can occur in specific situations even without any of the safeguards above.

The GDPR lists several derogations. Here are three examples. A transfer might occur under a “derogation”:

- If the data subject has given explicit, informed consent.

- If the transfer is necessary for important reasons of public interest.

- If the transfer is necessary in relation to legal claims.

Relying on a derogation is only suitable in exceptional circumstances and is not considered a long-term solution to data transfers.

Standard Contractual Clauses After Schrems II

A case known as “Schrems II” caused major problems for some companies using SCCs. Here’s a brief outline of Schrems II and its implications for using SCCs.

What Is Schrems II?

Schrems II is a July 2020 decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). The case involved Max Schrems, Facebook, and the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC).

In the Schrems II decision, the CJEU assessed whether the US adequacy decision, a certification framework known as “Privacy Shield”, was valid under EU law. The court also considered whether SCCs were a valid way to transfer personal data to the US.

Schrems II is one of the most important cases in data protection and has had profound consequences for international data transfers. The fallout from Schrems II is still unresolved.

Schrems II and Privacy Shield

In Schrems II, the court had to decide whether Privacy Shield could protect personal data from access by US intelligence services. To do so, the CJEU focused on two US surveillance laws, “FISA 702” and “EO 12333”.

Under these laws, the US government can access personal data controlled by US companies in a way the CJEU said was “beyond what is necessary in a democratic society”.

The Privacy Shield framework forced certifying companies to protect personal data to EU standards. But Privacy Shield did not override national law and could not protect people in the EU from surveillance under FISA 702 and EO 12333.

Because the framework could not protect personal data from US intelligence agencies, the CJEU decided Privacy Shield was invalid under EU law. EU organisations could no longer use the framework.

This presented a problem to the thousands of companies relying on Privacy Shield to facilitate international data transfers to the US.

Schrems II and Standard Contractual Clauses

In Schrems II, the CJEU also considered the implications of US surveillance law for SCCs.

The same fundamental problem applied to SCCs as to Privacy Shield. The court found that SCCs alone did not stop US intelligence agencies from accessing personal data.

The Schrems II decision did not say that using SCCs was illegal. But the court noted that using SCCs does not automatically make an international data transfer compliant with the GDPR. This finding applies to transfers to any third country—not just the US.

Since Schrems II, organisations must take additional steps to ensure that SCCs are valid.

European Data Protection Board Recommendations on Standard Contractual Clauses

Following Schrems II, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) published a set of recommendations about SCCs (Recommendations 01/2020).

The EDPB recommendations provide a step-by-step process to determine whether SCCs are valid, including carrying out a “transfer impact assessment” (TIA) and adopting “supplementary measures”.

What Is a Transfer Impact Assessment?

A transfer impact assessment (TIA) is a process of evaluating the legal framework and the practices of law enforcement agencies in the data importer’s country.

Remember that national laws generally override contracts, including those containing SCCs. And even where there are no such national laws in place, governments sometimes illegally intercept communications.

Before making a transfer, the EDPB recommends that data exporters assess whether “there is anything in the law and/or practices in force” in the importer’s country that could “impinge on the effectiveness” of the transfer mechanism (e.g. SCCs).

A TIA can be long and complicated and may require external legal advice. Following Schrems II, every EU organisation is required to undertake a TIA before conducting an international transfer.

What Are Supplementary Measures?

Supplementary measures are technical or organisational safeguards that can “supplement” the protection provided by SCCs.

For example, if you’re transferring personal data to a US-based organisation such as Google or Microsoft, the US government can force the company to provide access to the personal data. SCCs alone do not prevent government access.

However, if you also encrypt the personal data and ensure the US-based company cannot access the key, the personal data might be safe from surveillance.

Note, however, that there are no known effective supplementary measures for some very common types of data transfer.

Sometimes Supplementary Measures Don’t Work

The EDPB’s recommendations identify some hypothetical “Use Cases” in which supplementary measures might—or might not—apply.

For example, Use Case 1 involves an EU-based company using a hosting service provider in a third country to back up its data.

Here, SCCs could be valid if six strict conditions are met, including that the data was strongly encrypted before transmission and the importer could not access the keys. In this scenario, SCCs and supplementary measures could work.

Other examples are more problematic, namely Use Case 6 and Use Case 7. These scenarios are also among the most common examples of international data transfers.

Use Case 6 covers transfers to “cloud services providers or other processors which require access to data in the clear” (i.e. unencrypted or decryptable data). Access to data “in the clear” is essential for providing many cloud services.

Use Case 7 covers transfers “for business purposes including by way of remote access”. For example, a non-EU human resources (HR) services provider that needs access to unencrypted and non-pseudonymised data about employees.

In each example, the importer is in a country such as the US, where the TIA process has identified the need for supplementary measures.

But in these two examples, *there are no known supplementary measures that could be “added” to SCCs to protect personal data. Or as the EDPB puts it,

“…the EDPB is, considering the current state of the art, incapable of envisioning an effective technical measure to prevent… access from infringing on the data subject’s fundamental rights.”

Do I Need SCCs If Personal Data Is Stored in the EU?

An “international data transfer” can occur even if personal data never leaves the EU. If the data importer is subject to third-country laws, all the rules on international data transfers apply.

In a footnote of its recommendations, the EDPB notes that “remote access by an entity from a third country to data located in the EEA is also considered a transfer”. In other words, even if personal data is physically located in the EU (or the wider EEA), SCCs might not work.

This is due to laws such as the US CLOUD Act. The CLOUD Act requires electronic communications service providers (ESCPs) to provide US law enforcement access to data over which the ECSP has “custody, control, or possession”.

Here’s a real example: a 2021 German court case against RhineMain University of Applied Sciences. The university allegedly violated the GDPR’s data transfer rules by using a consent management platform (CMP) called Cookiebot.

Cookiebot employed A Technologies GmbH, a European subsidiary of US-based cloud provider Akamai, as a subprocessor. Although the subprocessor used EU-based servers, the court found that it fell within the CLOUD Act’s scope.

Therefore, the DPA found that the university’s use of Cookiebot violated the GDPR’s data transfer rules, even though the personal data remained on servers located in the EU.

Risk-Based Approach and Standard Contractual Clauses

Since Schrems II, there has been some debate over whether the GDPR allows for a “risk-based approach” to international transfers.

Here’s the central question in this debate: Do the GDPR’s rules apply to all international data transfers, or are some “low-risk” transfers exempt?

What Is the ‘Risk-Based Approach’?

The “risk-based approach” to international transfers suggests that some transfers could proceed lawfully even if there is a risk of law enforcement agencies accessing personal data.

Opponents of the “risk-based approach” argue that any risk of unauthorised access by third-country law enforcement agencies must be effectively eliminated before an international data transfer can proceed.

Several decisions from early 2022 onwards suggest that there is no “risk-based approach” to international data transfers.

Google Analytics Decisions and Standard Contractual Clauses

In January 2022, the Austrian DPA (known as the DSB) concluded an investigation of an online retailer that used Google Analytics.

The retailer relied on SCCs to transfer analytics data to Google. Google Analytics received seemingly non-sensitive, such as IP addresses and browser information.

Despite the apparently low risk, the DSB decided that the retailer had violated the GDPR’s international transfer rules.

Max Schrems’ campaigning organisation, noyb, was behind this and 100 other complaints against websites using Google Analytics.

“While there are many alternatives that are hosted in Europe or can be self-hosted, many websites rely on Google and thereby forward their user data to the US multinational,” noyb said in a press release.

In a second decision addressing Google directly, the DSB explicitly stated that the GDPR “does not recognise a risk-based approach” for international data transfers.

Other DPAs followed suit. French DPA made a similar decision against another website operator, followed by another two decisions in March. Further decisions followed in Italy and Denmark.

Each DPA found that Google Analytics users were breaking international transfer rules.

According to these decisions, even low-risk data requires EU-standard protection. And if you can’t eliminate the risk of government access, the transfer cannot proceed.

Case Study: Standard Contractual Clauses and AWS

Finally, let’s look at an example of how to assess whether SCCs are appropriate.

We’ll use Amazon Web Services (AWS) for this case study, but the same rules could apply to any US-based cloud services provider.

There are circumstances in which an EU-based organisation could transfer personal data to AWS lawfully. There are also circumstances in which such a transfer is likely to be unlawful.

Before transferring personal data to AWS, an EU-based company must follow the steps set out in the EDPB’s guidelines (discussed above). Let’s consider some of these steps as they relate to using AWS.

Assessing US Law

Before making a data transfer, the data exporter must assess the law of the importer’s third country. In this case, AWS should be treated as a US-based company, even though it has a Luxembourg-based subsidiary (AWS Sarl).

A full transfer impact assessment (TIA) would require extensive analysis of third-country law and practice. In this case, we can draw some conclusions based on Schrems II and subsequent enforcement action.

Schrems II confirmed that US law is problematic by EU standards, partly due to how US government agencies can access data under FISA 702 and EO12233. As noted above, the CLOUD Act also conflicts with EU law.

AWS is an electronic communications services provider (ECSP) and is subject to these laws.

As such, there is a clear risk of unauthorised access to personal data.

Contractual Measures

Amazon Web Services (AWS) and its EU-based users agree to the AWS GDPR Data Processing Addendum. This contract incorporates the latest SCCs. The agreement also includes a supplementary addendum published by AWS after Schrems II.

In its Data Processing Addendum, AWS provides some assurances about how it will respond to government access requests:

This paragraph states that AWS will:

- Share data following a “valid and binding order” by a government body.

- Attempt to “redirect” the government body to the user.

- Notify the user of any data disclosure unless “legally prohibited from doing so”.

So, AWS rightly acknowledges the risk of unauthorised law enforcement access to users’ data.

In a guide titled Navigating Compliance with EU Data Transfer Requirements, AWS claims that “the issue of national security access to their personal data is unlikely to arise because this data would not be of interest to national security agencies.”

This sentence suggests that data transfers to AWS are low-risk. Other companies, such as Google, have used similar language.

But we know from the Google Analytics decisions that EU DPAs do not accept the “risk-based approach” to international transfers.

On this assessment, it appears that SCCs alone are not enough to protect personal data transferred to AWS.

Supplementary Measures

Because SCCs alone cannot protect personal data from US government access, exporters should consider “supplementary measures” that could physically prevent AWS from providing personal data to the US government.

According to AWS documentation, the company offers a range of technical and organisational measures to protect users’ data, including encryption and encryption key management.

We have a real example of these supplementary measures being tested. In a March 2021 French court case, an e-health company called Doctolib was sued for transferring personal data to AWS Sarl.

The court found that the transfer did not violate the GDPR. But the circumstances were highly specific.

One factor in the court’s decision was encryption key management. AWS could not access Doctolib’s data because the keys were managed by a trusted third party based in France.

This solution will only be lawful in limited circumstances where AWS does not require access to user data for providing its services. For example, when using AWS for backup purposes, per the EDPB’s “Use Case 1” (explored above).

Third-party key management would not work where AWS or any other third-country company requires access to personal data “in the clear” (Use Cases 6 and 7). Such scenarios include common activities, such as providing customer services, web analytics, or marketing insights.

This case illustrates a key principle behind international data transfers: The effectiveness of SCCs depends on all the circumstances of the transfer.

If SCCs and supplementary measures cannot protect personal data from the risk of unauthorised access, the transfer cannot proceed.