Do Not Track (DNT) is back. A recent German court case against LinkedIn suggest that websites that track their users should recognise DNT signals or risk violating the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

First proposed in 2009, the DNT header sends a signal from a user’s browser to request that websites do not “track” the user’s activities across the web. DNT is enabled by default in some browsers, but many website operators ignore DNT signals.

So what’s changed? Should your website avoid forcing cookies upon users with DNT enabled? It’s complicated, but this article explains why it’s time to take DNT seriously.

LinkedIn’s Berlin Court Case

Peter Hense is the founder of Sprint Legal and part of the legal team behind the Berlin court case against LinkedIn.

Hense said the case should have a “major impact on tracking”—but he was not surprised by the outcome.

“The court stated the obvious and even quoted a bunch of legal commentaries on it,” Hense said. “They all agreed with DNT being a valid signal.”

LinkedIn did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The Case Against LinkedIn

LinkedIn was taken to court by the Federation of German Consumer Organisations (known as “VZBV”), which alleged that the company violated the law in two main ways:

- DNT signals: LinkedIn states that it does not respond to DNT signals and tracks users with DNT enabled.

- Profile visibility: LinkedIn users’ profiles are visible to non-LinkedIn users, and LinkedIn does not make it sufficiently easy for users to keep their profile information private.

We’re focusing on the first point, but the Berlin Regional Court broadly sided with the consumer protection group on both issues.

LinkedIn’s Tracking

LinkedIn uses various scripts, cookies, and “fingerprinting” techniques to measure and analyse how people use its platform.

These technologies also collect data about users’ activities on other websites and share that data with third parties.

The court considered whether LinkedIn (and, by implication, other websites and online services) was required to obey DNT requests under the GDPR.

To answer that, we need to explain how LinkedIn justified its tracking activities in the first place.

LinkedIn’s ‘Legitimate Interests’

Under the GDPR, organisations need a “legal basis” to collect or use (“process”) personal data.

One example of a GDPR legal basis is “consent”: A person permitted to process their personal data in a specific way. LinkedIn gets consent for some of its activities.

But for the relevant tracking activities, LinkedIn relies on the legal basis of “legitimate interests”.

You can read more about “legitimate interests” here. For our purposes, the most important thing to note is this: If you’re relying on legitimate interests, people have the right to object to what you’re doing with their personal data.

The Right to Object

Under the “right to object”, a person can ask a company to stop processing their personal data in specific ways.

The company has to comply with a request unless—unless it can demonstrate that it has “compelling legitimate reasons” to continue using the person’s data (unless it’s using the data for “direct marketing” purposes, in which case it has to comply no matter what).

Let’s put this in the context of DNT signals.

You operate a website. Someone visits your website with “DNT” enabled.

According to the consumer group behind the LinkedIn case, this user is submitting a request under the right to object, and you’ll normally have comply with that request.

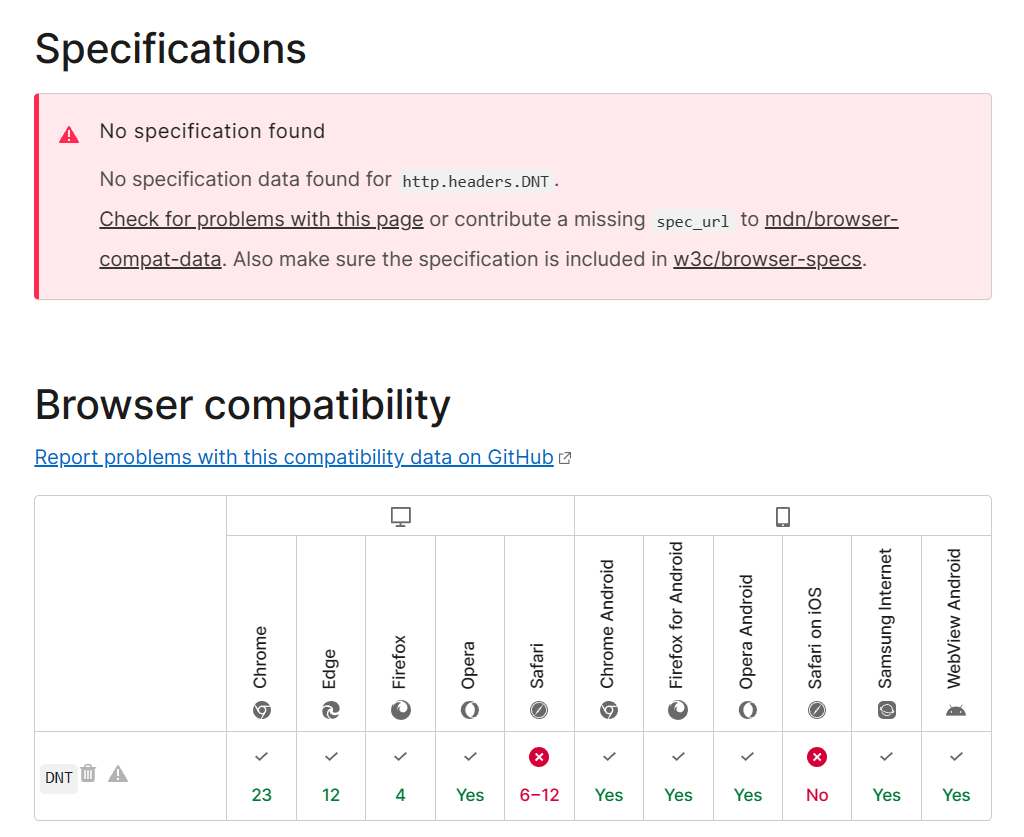

One of LinkedIn’s counterarguments was that DNT is not a widely-recognised standard—and, therefore, is not a valid request under the “right to object”.

Is DNT a ‘Recognised Standard’?

It’s true that the DNT standard has not seen widespread recognition across the web.

The Tracking Protection Working Group (TPWG) of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has long advocated for the legal recognition of DNT signals.

Since 2014, California has required website operators to disclose whether they honour DNT requests. This law, the California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA), is probably why LinkedIn included a DNT disclaimer in its privacy notice.

But that California law does not require website operators to actually do anything in response to DNT signals—it only requires them to explain whether they do anything. Unsurprisingly, most websites simply state that they ignore DNT requests and carry on tracking.

But while a disclaimer might be sufficient under CalOPPA, what about the GDPR?

Respecting the Right to Object

Under the GDPR, people can choose how to exercise their rights.

Organisations must make it easy for individuals to submit requests. Recital 59 of the GDPR says organisations should establish “modalities” for “facilitating the exercise” of people’s rights. Modalities might include a dedicated email address or web form.

But if someone makes a valid request via another route, the company must still respond to the request.

And in fact, Article 21 (5) of the GDPR states that a person “may exercise his or her right to object by automated means using technical specifications”. Doesn’t this include DNT signals?

According to Hense, this part of the law was “basically invented” or “lobbied into” the GDPR “to help DNT signals become a standard.”

“It’s a powerful section of this article, and the authors were very smart people,” Hense said.

Why is This Even Under Debate?

So if website operators have to consider requests under the right to object, including via “technical specifications”, why wouldn’t this include DNT signals?

“The problem is, no one has brought that to court before,” said Hense. “And marketers were just ignoring it.”

As Hense says: “The court stated the obvious.”

Technically speaking, the judge found that LinkedIn was misleading people in its privacy notice by implying that DNT signals were not a valid way to object. But by implication, this means that DNT signals are a valid way to object.

For now, the judgment only applies to companies operating in Germany. However, the relevant parts of the GDPR are the same in every other country that has implemented the law.

As such, website operators risk similar issues to LinkedIn if they fail to respect DNT signals.

LinkedIn intends to appeal, which might lead to a judgment from the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) which will settle the matter once and for all.

Rejecting Consent Requests

There’s another slight complication in this case.

As noted earlier, many website operators request consent before tracking users. This raises a related question: If a user sends a DNT signal, do this mean they do not consent to tracking?

While the distinction might seem trivial, refusing consent and exercising the right to object are different concepts under the GDPR.

The Berlin court did not explore this question, but Hense believes the judgment has implications for consent requests, too.

Hense argues that a website “can’t just have a CMP (consent management platform) pop up asking for marketing consent” if a user has sent a DNT signal. He argues that this would “an illegal (and) aggressive business practice” that violates EU consumer protection law.

This has a major impact on CMPs and tracking in general,” Hense says.

As such, if a user has DNT enabled, a website should arguably avoid tracking that user regardless of its “legal basis” for doing so.

Global Privacy Control (GPC): DNT 2.0

The German court case should bolster the DNT standard in Germany—and, arguably, the rest of the EU, the wider European Economic Area (EEA), and the UK.

And similar protocols will soon be legally mandatory across parts of the US.

The Global Privacy Control (GPC) is a successor to the DNT that provides similar privacy protections for users. Supporters say that GPC is also easier for websites to interpret.

In 2022, California’s Attorney General took enforcement action under the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) against a French cosmetics retailer, Sephora, partly because the company did not respond to GPC signals.

And over the next few years, recognising “universal opt-out” mechanisms, such as GPC, will be a legal requirement across the following states:

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Montana

- Oregon

- Texas

Each of these states has its own interpretation of the rules and several states will soon compile a list of legally mandatory opt-out signals.

But the direction of travel is clear: It’s time to start treating universal opt-out signals seriously—and configuring your website to recognise DNT signals is a great way to start.

UPDATE: LinkedIn’s Response

LinkedIn’s Senior Communications Manager, Charlene Zikmund, had that to say on the subject:

We disagree with the court’s decision which relates to an outdated version of our platform and intend to appeal the ruling.

Thanks, Charlene Verweij

Looking for web analytics that respect your users’ privacy while delivering value?