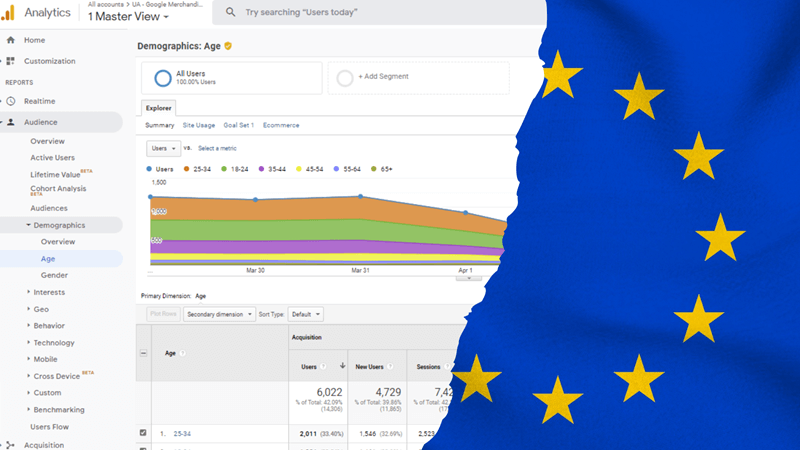

Meta Pixel and Facebook Login are used on thousands of websites across Europe. But a decision from the Austrian data protection authority (DPA) on 16 March revealed that websites using these tools could be breaking the law.

Over the past year, eight EU regulators have warned that another popular tool, Google Analytics, is incompatible with the GDPR. The Austrian DPA’s decision on Meta Pixel and Facebook Login raises similar issues—but there’s an important difference, too.

Here’s a look at what’s behind the Austrian DPA’s decision, and an explanation of why website and app operators may wish to reconsider their use Meta Pixel and Facebook Login.

The Background

The Austrian DPA’s decision comes after a 2020 complaint by privacy campaign group NOYB (“none of your business”), led by activist Max Schrems.

Schrems is best known as the man who brought down two “data transfer frameworks” in court battles with Facebook (now Meta) and the Irish DPA.

The Meta Pixel and Facebook Login case centres on a violation of the EU’s rules on international data transfers. Here’s a brief explanation of how these rules work.

Skip ahead if you already understand the EU’s data transfer issues.

Data Transfers 101

Under EU data protection law, businesses can only transfer personal data out of the EU under strict conditions. The rules aim to prevent people in Europe from being spied on by “third country” (non-EU) governments.

People in the EU have a fundamental right to privacy and data protection. But data must still sometimes move across borders. So, there are several mechanisms businesses can use to make their transfers safe and legal.

The most widely used transfer mechanisms are:

- An “adequacy decision”: The European Commission has assessed the data protection standards in a third country and declares those standards “adequate”.

- “Standard contractual clauses” (SCCs): A set of terms that can be inserted into a contract between an EU organization and a non-EU organization. The contract requires the non-EU organization to protect personal data to EU equivalent standards.

The ‘Schrems’ Cases

Like all “big tech” companies, Meta is based in the US. But thousands of EU companies transfer personal data to Meta every day, including via Meta Pixel and Facebook Login. Is this legal?

The US has a relatively intrusive surveillance regime and a weak data protection framework. The US does not have an “adequacy decision”.

But the European Commission and the US government have twice agreed upon special “data transfer frameworks”, known as “Safe Harbor” and “Privacy Shield”. Businesses that certified under these frameworks were legally required to protect personal data to a high standard.

The European Commission granted two adequacy decisions to the US, but they only applied to businesses certified under these frameworks. However, both adequacy decisions were overturned by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

In two cases, known as “Schrems I” and “Schrems II”, the CJEU found that the Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield frameworks did not protect people’s personal data from the US intelligence services.

But remember that an adequacy decision is not the only way to transfer personal data out of the EU. Another popular option is standard contractual clauses (SCCs). However, there are issues with SCCs, too.

The Problem With Standard Contractual Clauses

In the Schrems II case, the CJEU also considered whether SCCs were any better than Privacy Shield at keeping EU personal data safe.

The court found that SCCs did not work any better than Privacy Shield. US businesses bound by SCCs could still be forced to hand over personal data to the intelligence services.

Following Schrems II, organizations could still use SCCs to transfer data to the US—but they would need to put additional protections in place to ensure that the US-based company could not access the data in “plain text”.

The problem for companies like Meta and Google is that they need to access personal data to provide their services and sustain their business models.

As such, many companies using Meta and Google’s services have been transferring personal data without appropriate safeguards in place.

Meta Pixel and Facebook Login Privacy and Security Risks

As noted, the Austrian DPA’s decision focuses on data transfers. We’ll explore that below. But beyond data transfers, there are other issues with using Meta Pixel and Facebook Login. Let’s briefly look at these first.

Meta Pixel’s Data Harvesting Habits

Meta Pixel is a piece of code that measures how people interact with ads on a website. The tool is used on thousands of websites, including those operated by hospitals, schools, and governments.

Meta Pixel can also link individual website visitors to their Facebook accounts. This presents a privacy risk, particularly as many organizations do not obtain consent before using the tool.

Regulators have targeted businesses using Meta Pixel before. In the first two months of 2023, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sanctioned two telehealth companies that were sharing highly sensitive personal data with Meta by using Meta Pixel.

These privacy issues were not central to the Austrian DPA’s decision—but they are important for anyone considering using these tools.

Facebook Login: Privacy and Security Risks

Facebook Login is a single sign-on (SSO) tool that enables Facebook users to log into a third-party website or app via a Facebook account rather than creating a new account for that website or app. Other platforms, such as Google and Twitter, also offer SSO tools.

Using Facebook Login is quick and convenient. Users no longer have to create a new account with each website or app they want to log into. Service providers might add Facebook Login to reduce friction in the account creation process, which might attract more users.

But there are significant privacy and security risks associated with Facebook Login.

When Facebook suffered a hack in 2018, it compromised over 50 million “account tokens”. Bad actors could have used these tokens to log into people’s Facebook accounts—and any third-party account that a user created via Facebook Login.

Facebook Login also collects data about how people use third-party sites. Dating app Bumble used to rely entirely on Facebook Login. But the app changed this policy in 2018, so its users could use Bumble “without having to share (their) data with Facebook”.

Three Takeaways From Austrian DPA’s Meta Decision

The Austrian DPA’s decision came in response to one of the 101 complaints submitted by NOYB, all of which concerned either Google Analytics or Facebook Business Tools.

The DPA’s decision is not aimed directly at Meta.

The complaint was directed towards a news website that had integrated Meta Pixel (then “Facebook Pixel”) and Facebook Login into its website. The operator of that website—not Meta—was held liable for the GDPR compliance issues associated with Meta’s tools.

Let’s look at three important takeaways from the Austrian DPA’s decision.

Meta Pixel and Facebook Pixel Collect Personal Data

To establish whether the GDPR was relevant to this case, the Austrian DPA had to determine whether Meta Pixel and Facebook Login collect personal data. As mentioned above, the answer is “yes”: These tools collect personal data—and quite a lot of it.

The DPA found that Meta Pixel collects the following data:

- HTTP header information, including:

- IP address

- Web browser information

- Page location

- Document

- Referrer (i.e. the website via which the user reached the current website)

- “Person using the website” (Meta’s own words)

- Pixel ID

- Facebook cookie

- Button click data:

- Any buttons clicked by the user

- Labels of those buttons

- Any pages visited via buttons

- Form field names (e.g. labels on web forms such as “email”, “address”, etc.

Developers can also collect more information with Meta Pixel via Meta’s “Custom Audiences” and “Advanced Matching” features.

The DPA found that Facebook Login collects the following data:

- IP address

- User agent string

- Mobile operating system and browser

- Information about the third-party website

- Visit date and time

- Website language

- Location (e.g. country)

- Website URL

- Screen resolution

- User ID

- Cached access tokens

- Other technical website data

- Cookie data

Meta can see all this data in plain text, and it was all being sent to Meta’s US servers.

Some of this information might not be “personal data” in isolation. However, any of the above information can be personal data when associated with an individual.

For example, data such as screen resolution and mobile browser type can be used for “fingerprinting”—identifying a user even without reference to a username or ID when combined with additional data points. The date and time of a website visit, when linked to an individual, can reveal information about that individual.

Meta Did Not Have Any Transfer Safeguards In Place

The Austrian DPA found that Meta was subject to US surveillance laws known as “EO 12223” and “FISA 702”. These laws would require Meta to hand over personal data to the US intelligence services on demand.

The DPA also found that Meta had not implemented any technical measures that would prohibit access to personal data by the US intelligence services.

NOYB lodged its complaint against Meta in August 2020. This was after the Schrems II case and the invalidation of Privacy Shield. But it was before Meta had put any alternative transfer mechanism in place.

Meta did eventually create an addendum to its data processing agreement that included SCCs. But this new agreement was not in place at the time of the complaint. Meta still claimed to be relying on Privacy Shield, which was invalid at the time.

As such, the Austrian DPA found that the website’s transfer of personal data to Meta was unlawful.

But remember: ultimately, in this case, the responsibility to ensure transfer safeguards were in place was on the website using Meta’s tools—not Meta itself.

The Problem Would Likely Have Remained Even With SCCs

Because there were any transfer safeguards in place at the time of the complaint, it’s unarguable that the website was breaching the GDPR’s data transfer rules by transferring personal data to Meta.

But what if NOYB had lodged its complaint later, once Meta had implemented SCCs? The outcome would almost certainly have been the same.

We know this from the Google Analytics decisions. Google had SCCs in place, but the company could still access EU-originating personal data in plain text. Therefore, companies using Google Analytics were still found to be violating the GDPR.

Even now, with SCCs in place, Meta does not appear to have implemented the technical measures necessary to protect people’s data.

Therefore, using Meta Pixel or Facebook Login is most likely still illegal under the GDPR.