In the run-up to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) enforcement deadline on 25 May 2018, the law’s increased fines made many headlines.

But some data protection advocates claim that the GDPR is failing in its central goal—improving data protection for people and businesses across Europe.

This article explores the GDPR’s enforcement mechanisms, considers the differing approaches of regulators across Europe, and addresses the “elephant in the room”: Is GDPR enforcement working?

GDPR Gatekeepers: The Data Protection Authorities

The GDPR is enforced by the data protection authorities (DPAs). Each country in the European Economic Area (EEA), plus the UK, has at least one DPA.

A representative from each DPA sits on the European Data Protection Board (EDPB). Among other things, the EDPB produces guidelines and recommendations on GDPR compliance, advises the European Commission on data protection, and deals with disputes between DPAs.

DPA Powers

Besides fines, there are many other “corrective powers” available to DPAs under Article 58 of the GDPR, including the following:

- Issuing warnings and reprimands.

- Ordering a controller or processor to:

- Comply with a data subject rights request.

- Bring its processing into GDPR compliance before a deadline.

- Notify data subjects about a data breach.

- Stopping the flow of personal data outside of the EEA.

- Banning a controller or processor from processing personal data altogether, either temporarily or permanently.

That last point—the power to order an organisation to stop processing personal data altogether—is particularly powerful.

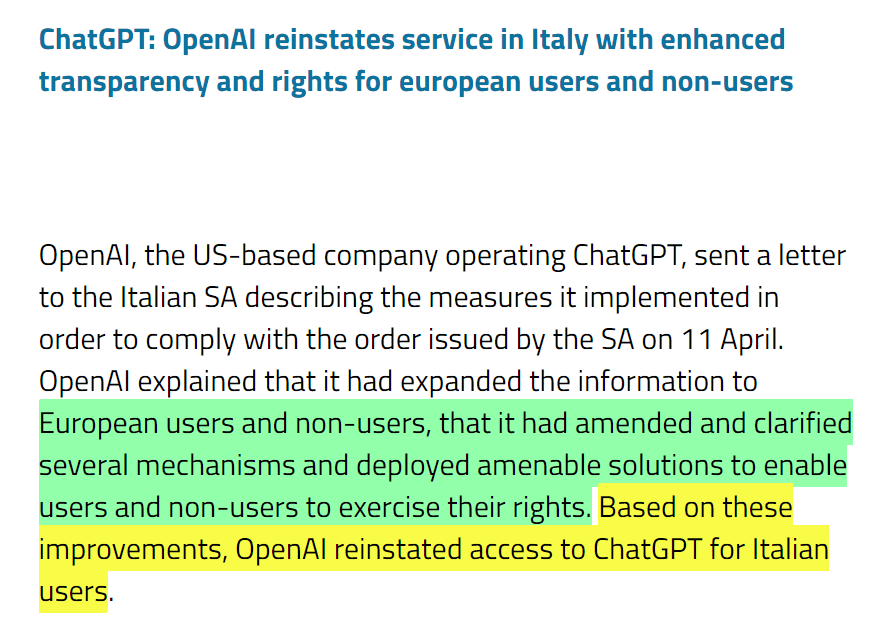

The Italian DPA used this power in April 2023 when it temporarily ordered OpenAI to stop processing the personal data of people in Italy via ChatGPT.

OpenAI was allowed to restart processing operations a few weeks later, after providing expanded privacy information, setting up a new data subject rights request process, and allowing EU users to opt out of having their personal data used for training the AI.

Different Approaches

Europe’s DPAs differ substantially in their approaches to GDPR enforcement.

Here’s a brief analysis of the differences between DPAs in some of the larger European states (plus Luxembourg) based on data from the (unofficial) GDPR Enforcement Tracker.

- Spain is by far the most active DPA in Europe, having issued 738 of the 2,032 decisions registered. Most of Spain’s penalties are small, and many are issued against small businesses and individuals.

- Italy is the EU’s second most active DPA and takes credit for 297 of the decisions. Many of these fines are relatively high—with 17 of them raising Italy over €1 million.

- The UK has issued just 13 GDPR decisions despite being one of the larger and better-funded European regulators. The ICO prefers to issue reprimands and has doled out 24 of them so far in 2023.

- Ireland imposed the highest GDPR fine of all time—€1.2 billion, against Meta. Ireland has issued six of the seven largest GDPR fines ever—six were against various Meta platforms, and one was against TikTok.

- Luxembourg issued the second biggest-ever GDPR fine (€746 million, against Amazon), but is otherwise a fairly timid regulator—all but one of its 31 other penalties are under €19,000.

- France occupies the final three spots in the top ten fines, but a French legal quirk means these penalties were technically issued for violating cookie rules under the ePrivacy Directive.

Is the GDPR Enforced Effectively?

Even the GDPR’s biggest fans criticise one aspect of the regulation: Enforcement.

“Five years into the GDPR, we see a lot of resistance by authorities and courts to enforce the law,” said Max Schrems, the privacy campaigner behind many of the most important GDPR enforcement decisions.

“It often feels like there is more energy spent in undermining the GDPR than in complying with it.”

Schrems’ campaign group, noyb (“None of Your Business”), has submitted more than 800 complaints since the GDPR took effect in 2018. Noyb’s own figures show that the vast majority of these complaints—over 85%—have not yet been decided.

So what’s the hold-up?

GDPR Enforcement Bottleneck

Any data protection campaign group, the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL), claims that the GDPR is at a “crisis point” in its fifth year of enforcement.

“The GDPR provides strong investigation and enforcement powers to protect people from the misuse of data that enables much of the digital world’s problems,” said Johnny Ryan, senior policy officer at the ICCL.

“It should be our shield against the digital era’s problems: discrimination, manipulation, media distortion, and invasive AI. But that shield has yet to be taken up.”

The ICCL’s research points to one central problem: the Irish DPA.

“Ireland continues to be the bottleneck of enforcement: it delivers few draft decisions on major cross-border cases,” Ryan claims. “When it does eventually do so, other European enforcers then routinely vote by majority to force it to take tougher enforcement action.”

Irish ‘Bottleneck’

The ICCL’s research supports the group’s claim that the Irish DPA, the Data Protection Commission, is causing a slowdown in “cross-border” GDPR enforcement (decisions involving data subjects and regulators from multiple EU member states).

Many US tech corporations have chosen Ireland as their European home, including:

- Meta (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp)

- Airbnb

- Yahoo!

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Microsoft (which owns LinkedIn)

- Apple

- Tinder

At the time of the ICCL’s research (May 2023), 87% of cross-border GDPR complaints to the Irish DPA reportedly involved these eight companies.

But the Irish DPA’s own statistics show that 83% of its cross-border complaints (as of September 2022) were resolved via “amicable resolution in the interests of the complainant”.

Author Martin McMahon shared his experience of the Irish DPA’s “amicable resolution” process on X.

McMahon complained to the Irish DPA about the Irish Department of Social Protection. He alleges that the Irish DPA spent four years going back and forth between him and the controller, seeking responses to the complaint, responses to the other side’s responses, and so on.

“This is never-ending,” McMahon said. “The aim is simple, (to) wear you down. If you don’t reply to a reply of a reply, you lose, the other side wins.”

The One-Stop Shop

Besides amicable resolution, the ICCL cites another reason for the slow progress of GDPR complaints: The “one-stop shop”.

The one-stop-shop intends to harmonise the application of the GDPR across the EU.

“The one-stop-shop mechanism is designed to reduce the administrative burden for organisations and make it simpler for individuals to exercise their rights from their home base,” says the EDPB.

Here’s an example of how the one-stop shop works (in theory):

- Maria lives in Spain. She submits a complaint to the Spanish DPA, claiming that a US company (Elgoog) has failed to respond to her subject access request.

- The Spanish DPA conducts a preliminary investigation and finds that the issue affects data subjects in multiple EU member states.

- The Spanish DPA must forward Maria’s complaint to Elgoog’s “lead supervisory authority”. Elgoog’s main EU establishment is in France, so its lead supervisory authority is the French DPA.

- As lead supervisory authority, the French DPA will lead the investigation into Elgoog. Elgoog should only have to deal with the French DPA, while Maria should normally only have to deal with the Spanish DPA.

- The French DPA must consult with other DPAs who might be affected by the decision. These other DPAs are known as “concerned supervisory authorities”. The French DPA and the other concerned supervisory authorities must agree to a final decision concerning Elgoog.

- The French DPA submits a draft decision to the EDPB, proposing to fine Elgoog €1 million. However, several concerned supervisory authorities want to fine Elgoog €2 million.

- The DPAs cannot agree, so the EDPB must adopt a “binding decision”. Following a vote, the French DPA is directed to fine Elgoog €2 million.

- The French DPA issues a final decision, fining Elgoog €2 million. The Spanish DPA communicates the outcome to Maria.

It’s a long process—but clearly designed to simplify GDPR enforcement for both the data subject and the organisation. However, the one-stop shop tends to be very slow when DPAs disagree.

No Cookie Banners. Resilient against AdBlockers.

Try Wide Angle Analytics!

Binding Decisions

The ICCL claimed that as of May 2023, 67% of Ireland’s cross-border decisions were “overruled” by the EDPB via the one-stop-shop process.

This statistic refers to cases when the Irish DPA could not reach an agreement with other DPAs and was subject to a “binding decision”. A binding decision directs one DPA to make certain findings or issue certain orders as agreed by the majority of the EDPB.

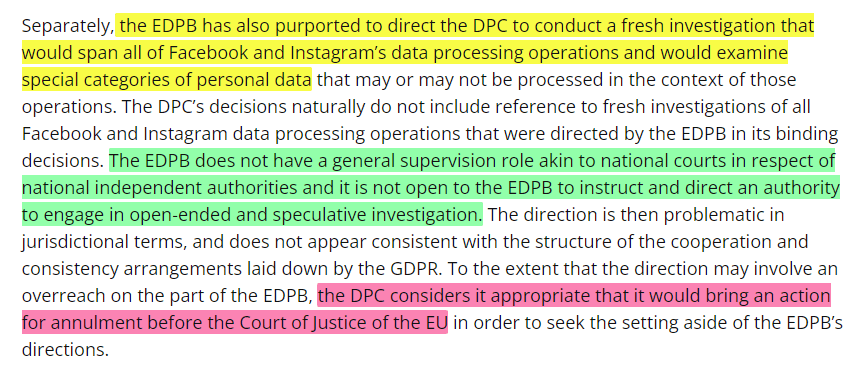

In January 2023, after finally concluding an investigation into Meta that took nearly five years, tensions between the Irish DPAs and its fellow regulators reached boiling point.

As part of a binding decision, the EDPB directed the Irish DPA to extensively re-write its Meta decision to find various violations that Ireland did not initially propose and increase the company’s fine.

But the EDPB also told Ireland to conduct a further investigation into how Meta processed “special category data” within Facebook and Instagram.

The Irish DPA refused, calling the proposed investigation “open-ended and speculative” and asserting that the EDPB was reaching beyond its legal powers. As such, the Irish DPA has taken the EDPB to court.

How GDPR Fines Work

Now, let’s take an in-depth look at fines under the GDPR (sometimes called “administrative fines” or “monetary penalties”).

Lower and Upper-Tier Fines

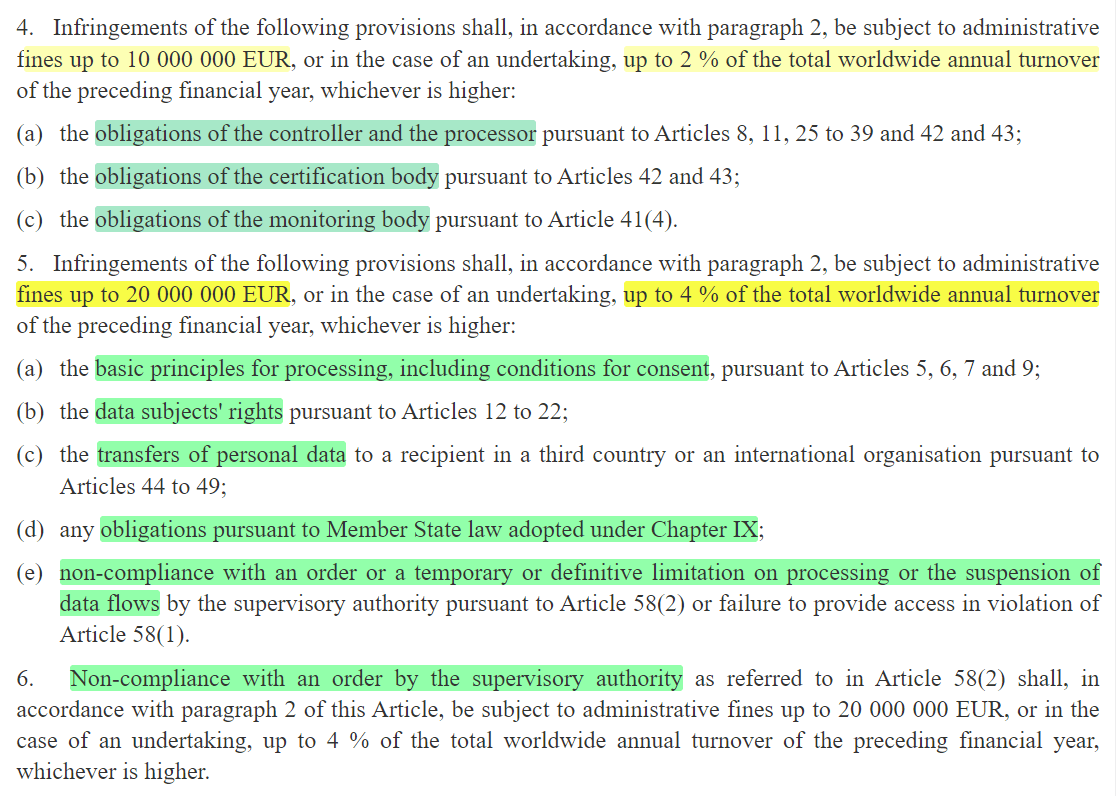

Here’s most of what the GDPR says about fines, at Article 83:

As you can see, there are two tiers of fines, which we’ll call “lower-tier” and “upper-tier”.

Lower-Tier Fines

“Lower-tier” fines can reach up to:

- €10 million, or

- 2% of total worldwide annual turnover of the previous financial year.

Lower-tier fines cover violations such as the following:

- Failing to obtain parental consent before processing children’s data when required to do so (Article 8).

- Failing to implement “data protection by design and by default” (Article 25).

- Failing to notify the DPA about a data breach in good time (Article 33).

Despite being associated with the lower tier of fines, some of the above violations can be quite serious. However, most GDPR decisions cite multiple violations, including some from the upper tier.

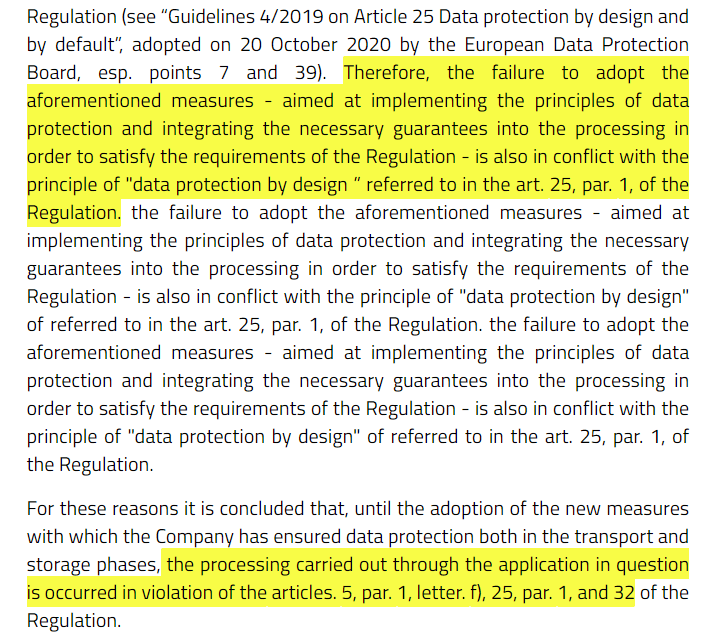

For example, failing to implement “data protection by design and by default” is often also seen as a failure to abide by the principles of data processing.

Here’s one of many such cases from the Italian DPA. An airport used an app designed to help whistleblowers report wrongdoing within the company. But the app was not suitably secure, creating a risk that whistleblowers could be identified.

The DPA found that the airport had violated its obligations under data protection by design. But the regulator also found violations of the principle of “confidentiality and integrity” and the controller’s security obligations. As such, the upper tier of fines was available.

Upper-Tier Fines

“Upper-tier” fines can reach up to:

- €20 million, or

- 4% of the organisation’s total worldwide annual turnover of the previous financial year.

These sorts of fines cover violations such as the following:

- Failing to abide by the principles of data processing (Article 5).

- Violating data subjects’ rights (for example, by failing to respond to a data subject access request on time) (Articles 12-22).

- Illegally transferring personal data to a country outside of the EEA (Articles 44-49)

The largest GDPR fine of all time, €1.2 billion against Meta by the Irish DPA in May 2023, was due to a serious and repeated violation of the final point above (international data transfers).

Calculating the Fine

GDPR fines must be:

- Effective (a meaningful way of enforcing the GDPR)

- Proportionate (fair, given all the relevant circumstances)

- Dissuasive (big enough to deter similar conduct among other organisations)

But how much is a GDPR fine normally worth?

The Five-Step Process

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has created guidelines on calculating GDPR fines. The EDPB provides a five-step process for DPAs when calculating GDPR fines.

- Identify the processing operations.

- Identify the starting point for the fine.

- Evaluate any aggravating and mitigating factors

- Identify the maximum possible fine.

- Assess whether a fine would be effective, proportionate, and dissuasive and make any necessary adjustments.

The EDPB provides a table to help DPAs find the “starting point” for a given fine. Here’s part of the table, which shows how to calculate the starting point for upper-tier fines of varying seriousness across companies with different turnovers.

Now, we’ll consider some examples of how GDPR fines work in practice.

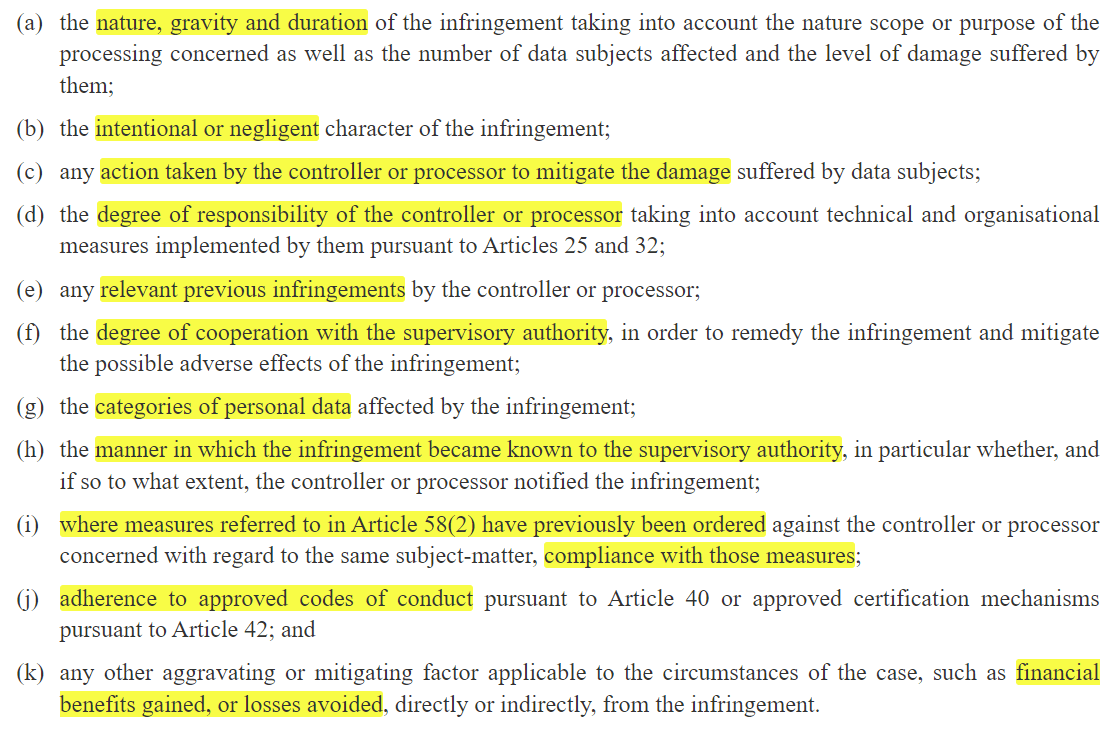

Aggravating and Mitigating Factors

DPAs can consider certain factors when deciding how much a fine should be. These factors are listed at Article 83:

Broadly speaking, an organisation can reduce its potential fine if it takes proactive steps to put things right, notifies the DPA of its violation, and cooperates with the DPA throughout the investigation.

Intentional GDPR violations, repeated offences, and breaches of sensitive or “special category data” attract harsher penalties.

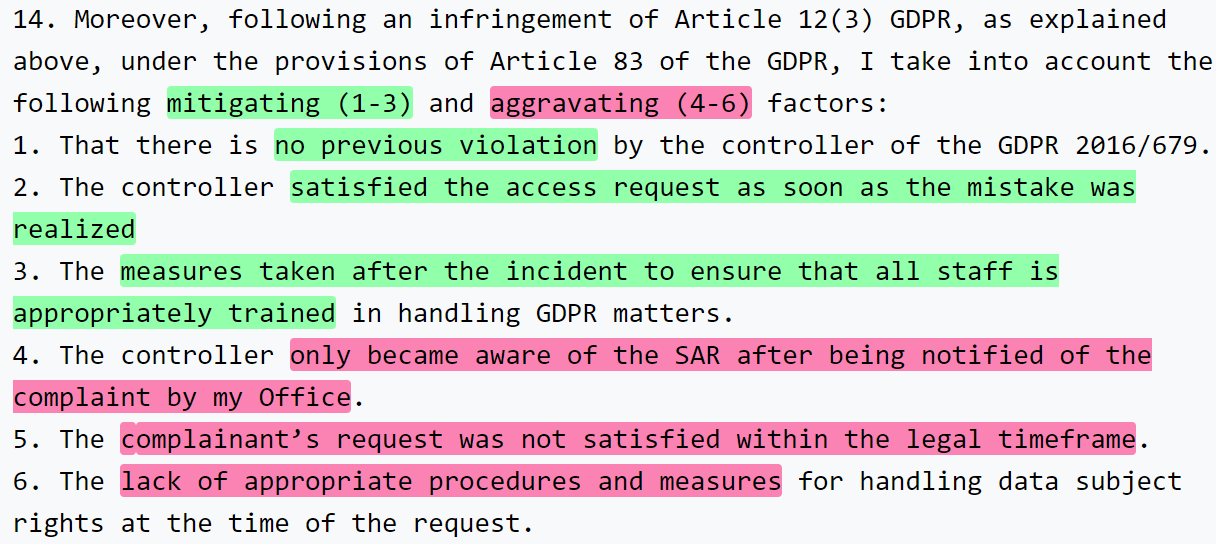

Here’s an example from Cyprus, in a case against Tarlun Ltd, which became the subject of a GDPR investigation after failing to respond to an access request.

Here, you can see how the DPA weighs up the mitigating and aggravating factors:

In Tarlun’s favour, the company:

- Had no history of GDPR violations.

- Corrected its mistake once it became aware of it.

- Put staff training in place to avoid future issues.

On the other hand, Tarlun:

- Only became aware of its violation once it had been contacted by the DPA.

- Did not fulfil the access request within the one-month timeframe

- Lacked any data subject rights procedures at the time of the request.

Violation-Stacking

GDPR violations “stack”. If a controller violates multiple parts of the GDPR (as is almost always the case when something goes wrong), a DPA will normally calculate a fine for each violation and add them together.

The GDPR says that where multiple violations have occurred, the total fine “shall not exceed the amount specified for the gravest infringement”. This rule refers to the maximum possible amount that can be issued, such as 2% or 4% of turnover.

Here’s a good example from July 2021 in Finland, where Psychotherapy Centre Vastaamo Oy suffered a serious data breach.

As shown above, the DPA calculated fines for three individual GDPR violations:

- Failing to notify the DPA on time (€145,600)

- Failing to notify data subjects on time (€145,600)

- Failing to abide by the “confidentiality and integrity” principle (€316,000)

The total fine was, therefore, €608,000.

‘Whichever Is Higher’

As noted, fines can be either a specific amount or a percentage of annual revenues. The fine can be “whichever is higher” of these two amounts.

Smaller companies arguably get a bad deal here. A fine of €20 million might represent a much higher proportion of a company’s annual revenues than 4%.

In the above case, the Finnish psychotherapy centre’s turnover was €14,627,478. So, the fine of €608,000 represented 4.2% of the company’s annual turnover.

Compare this to the 2021 fine against Amazon, from the Luxembourg DPA. At €746 million, Amazon’s was the highest GDPR fine ever issued at the time. However, the penalty only represented around 0.2% of Amazon’s turnover for the preceding year (€362.6 billion).

Large Enterprises

Where a controller or processor is part of a larger company, DPAs generally calculate the fine according to the turnover of the entire corporate group.

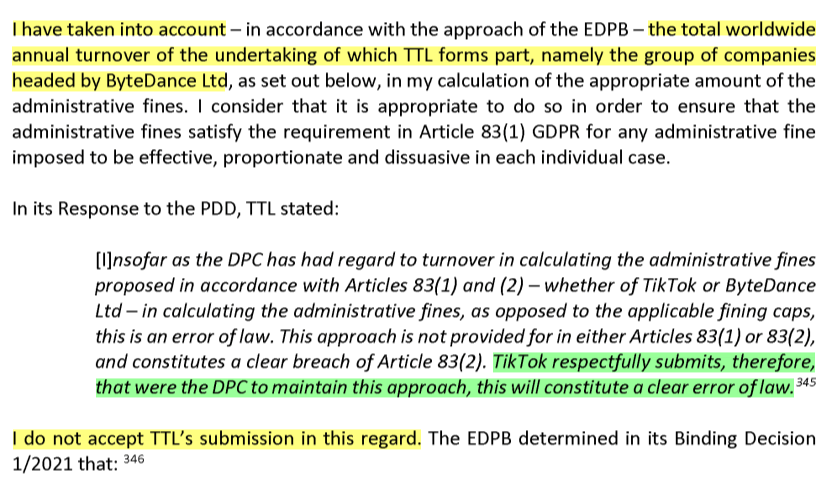

For example, in the September 2023 decision against TikTok, the Irish DPA had to decide whether to calculate the fine against the turnover of TikTok Ltd (TTL) or TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance.

TikTok argued that Ireland should only consider the smaller company’s turnover rather than the parent company. The Irish DPA and the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) disagreed.

As such, TikTok received a €345 million fine—just 0.45% of ByteDance’s turnover (approximately €75 billion in 2022) but around 3.7% of TikTok’s (approximately €9.9 billion).

The Future of GDPR Enforcement

Citing multiple issues with cross-border enforcement, the European Commission has drafted a regulation to reform the GDPR’s one-stop shop process, known as the Procedural Regulation.

According to the Commission, the Procedural Regulation will:

- Provide a standardised form for cross-border complaints

- Bring new, standardised rules regarding the involvement of various parties to a complaint.

- Create a new cooperation and consistency process that encourages cooperation between DPAs.

- Put deadlines in place to speed up the resolution of complaints.

While GDPR enforcement remains slow and uneven across the EU, fines are increasing. According to research by law firm DLA Piper, the total amount of fines issued last year rose by 50% on the preceding year—and was more than double 2021’s figure.

The research also found that data breach notifications have fallen, suggesting that increased enforcement might be affecting real-world improvements.

This increase in regulatory activity, together with the reforms proposed in the Procedural Recommendation, could make the GDPR’s goals of harmonising and enhancing data protection standards a reality—even if the improvements arrive later than initially predicted.

No Cookie Banners. Resilient against AdBlockers.

Try Wide Angle Analytics!