The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) provides strict rules dictating how and when personal data can be transferred to a person in a country outside of the European Economic Area (EEA) (or, under in the UK GDPR, outside of the UK).

Generally speaking, an international data transfer can only occur when the “data importer” is in a country covered by an adequacy decision or when the exporter and importer have implemented appropriate safeguards such as standard contractual clauses (SCCs).

But if there’s no adequacy decision and none of the appropriate safeguards are available, you might be able to rely on a “derogation”—an exception to the usual rules on international data transfers.

This article provides four basic principles for using the derogations and explores each derogation in depth, with reference to authoritative sources such as the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), and—of course—the GDPR itself.

Outline of the Derogations

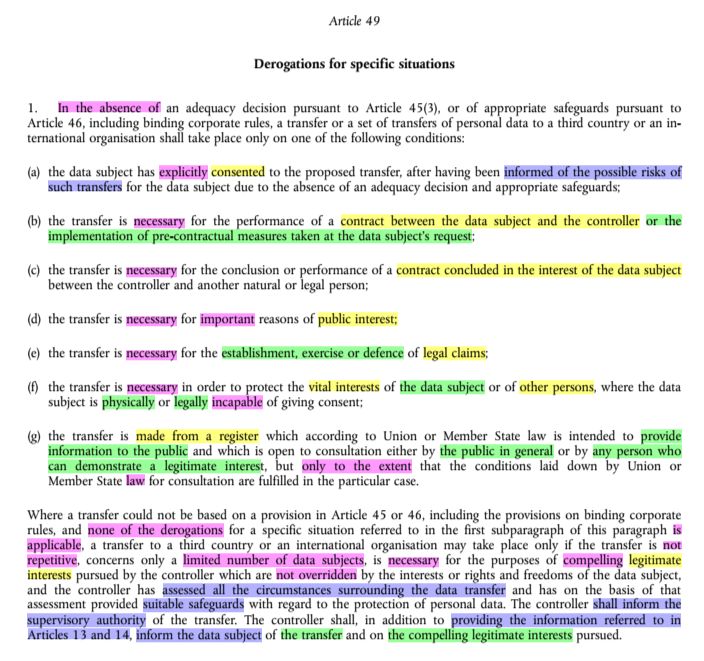

First, let’s look at Article 49 (1) of the GDPR, which provides the list of international transfer derogations.

We’ve highlighted some important parts of the law. Here’s what each colour means:

- Yellow: Main provision

- Pink: Rules and conditions

- Green: Examples, specifications, and exceptions

- Purple: Required actions

Article 49 contains some other conditions on international data transfer derogations, which we’ll explain throughout the article, where relevant.

Don’t worry about studying these excerpts too closely—we’ll walk you through the important parts throughout this article. You can come back to this section if required.

The Eight Derogations

We’ll refer to the eight international data transfer derogations as follows:

- Explicit consent

- Contract with the data subject

- Contract benefitting the data subject

- Public interest

- Legal claims

- Vital interests

- Public register

- Compelling legitimate interests

Later in the article, we’ll look at some of these derogations in detail. But first, here are some general rules and principles that apply to the derogations.

Four Basic Principles For Using the Derogations

1. The derogations are a last resort

International data transfer derogations must only be used in exceptional cases. This is reiterated in the EDPB’s Guidelines 2/2018 on derogations of Article 49 under Regulation 2016/679:

“…the derogations must be interpreted restrictively so that the exception does not become the rule. This is also supported by the wording of the title of Article 49 which states that derogations are to be used for specific situations…”

When you’re considering a new project or choosing a new service provider, relying on a derogation should not normally be part of the plan.

The GDPR says that the derogations are only available “in the absence of” either an adequacy decision or one of the GDPR’s “appropriate safeguards”, such as SCCs.

So before even considering the derogations, you must establish that there is no other possible legal route for your international data transfer. You must document this assessment.

Here’s an example of the sort of process you might go through before considering a derogation:

- You intend to transfer personal data to a destination country outside the EEA (a “third country”).

- You note that the destination country does not have an adequacy decision.

- You consider whether SCCs would be appropriate.

- You conduct a transfer impact assessment (TIA).

- The assessment reveals that the exported data would be accessible to public authorities in the destination country.

- You establish that the destination country’s laws are not “essentially equivalent” to EU standards.

- You determine that there are no “supplementary measures” that would safeguard the personal data.

At this point, you must either:

- Suspend the transfer. Look for options in the EEA or an “adequate” country, or

- Assess whether a derogation applies, and record this assessment.

2. Important conditions apply when using the derogations

Although the derogations are designed for exceptional situations, there are still important conditions that apply in each case.

Firstly, most of the derogations can only be used when transferring personal data to a third country is “necessary” for a specific purpose.

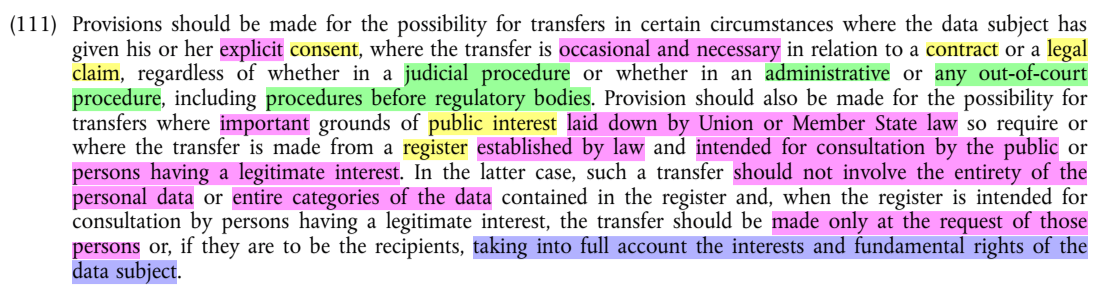

Secondly, most of the derogations are only to be used on an “occasional” basis. This is stated at Recital 111 of the GDPR:

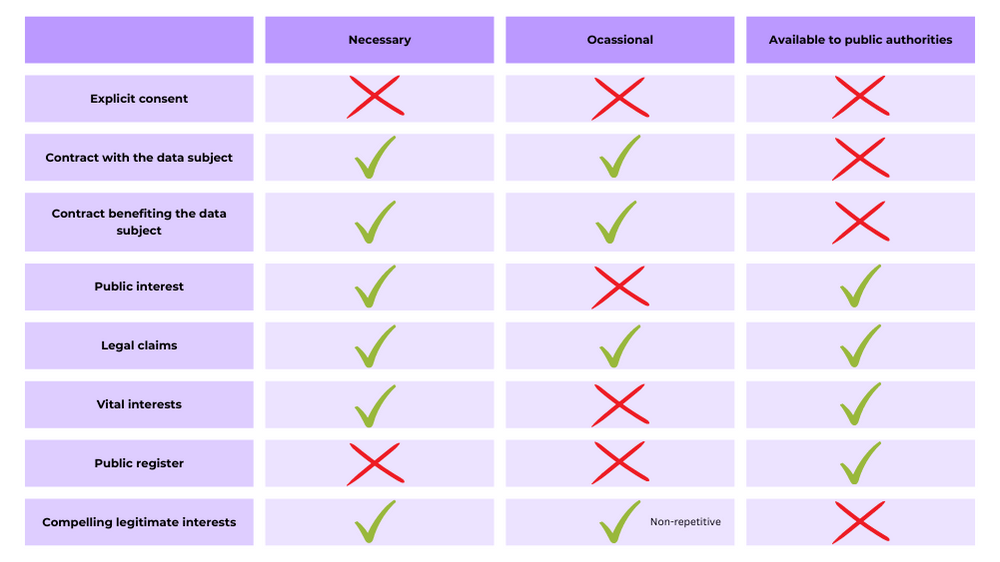

The table below shows which derogations are only for “necessary” and/or “occasional” transfers. We’ve also indicated which derogations are available to public authorities when exercising their powers.

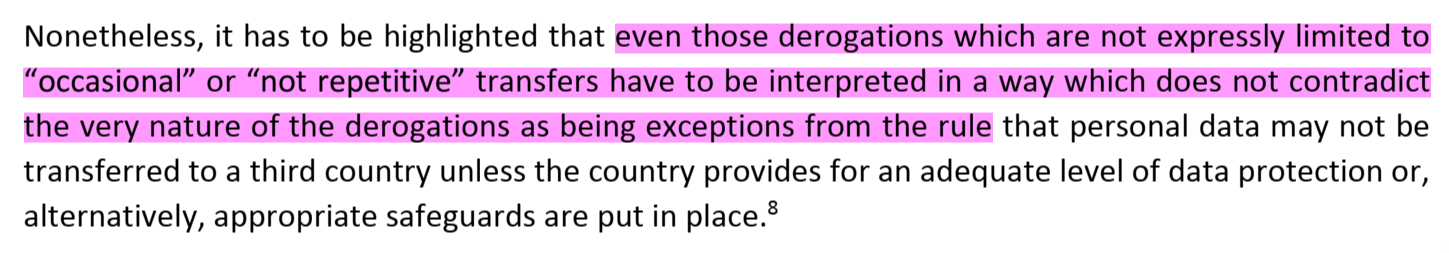

But even where a transfer is not listed as “necessary” or “occasional”, it should still be treated as exceptional—as noted by the EDPB:

3. No additional data transfer safeguards are required when relying on (most) derogations

Because the derogations are intended for exceptional situations in which no appropriate safeguards are available, you do not need to put “supplementary measures” in place when relying on a derogation—with one exception.

The exception to this rule is the “compelling legitimate interests” derogation, which you cannot use unless you have taken strict safeguarding steps. We’ll look at this derogation in detail later in the article.

The EDPB reminds us that “transferring personal data to third countries on the basis of derogations leads to increased risks (for individuals)” and that other transfer mechanisms should always take precedence where possible.

4. All of the GDPR’s other rules and principles continue to apply

As noted, the derogations allow for international data transfers even where no special contractual or technical transfer safeguards can be put in place.

But all the GDPR’s other rules and principles still apply. Among other things, this means:

- You must not process personal data unless necessary for a specified purpose (including by transferring it to another organisation).

- You must have a legal basis for processing (which includes making an international data transfer).

- You must apply appropriate security measures (Article 32 of the GDPR, which sets out the law’s security requirements, still applies—even if you cannot implement appropriate safeguards specific to the transfer).

Now let’s look at how each of the international data transfer derogations works.

Explicit Consent

The first international transfer derogation is known as “explicit consent”. The explicit consent derogation applies where the data subject has:

- Explicitly consented to the proposed transfer.

- Been informed of the possible risks of the transfer.

Let’s consider each of these two elements in turn.

The ‘Explicit’ Threshold

Consent under the “explicit consent” derogation is stricter than the GDPR’s normal concept of “consent”.

The “explicit” condition applies in addition to the GDPR’s normal consent conditions. Read our main article on GDPR consent to learn more.

But what does “explicit consent” mean in practice?

Here’s an example from the EDPB:

Let’s apply this example to a hypothetical scenario:

- A German ecommerce company collects a customer’s personal data.

- The company requests the customer’s consent to use the personal data for the purposes of delivering a product (Note: This would not normally be the right legal basis for this activity, but this is the EDPB’s example).

- Later on, the company decides to use a Brazilian logistics firm to help manage deliveries.

- To use the Brazilian logistics firm, the German company needs to transfer the customer’s personal data to Brazil.

- After exhausting all other options, the German company considers using the explicit consent derogation.

The customer’s initial consent (for delivery) would not cover this data transfer. The German company would need to return to the customer and request explicit consent for the data transfer.

The ‘Informed’ Threshold

Under the explicit consent derogation, you must also inform the data subject of the “possible risks” associated with the transfer. These risks arise because:

- The destination country does not have “adequate” data protection standards, and

- You have not put appropriate safeguards in place to protect the personal data once it reaches the destination country.

According to the EDPB, this includes informing the data subject of the following sorts of risks, if they are relevant to the destination country:

- There is no independent data protection authority.

- The principles of data processing will not apply.

- The data subject rights will not be available.

And remember, the above rules are on top of the GDPR’s other provisions.

The GDPR’s general transparency requirements (Articles 12-14), apply whenever you obtain personal data.

When you request consent, Recital 42 of the GDPR says that you must tell the data subject, at a minimum, who you are, and what you intend to do with their personal data if they consent.

Case Study: Meta

The international transfer derogations are, by their nature, used rarely. But they came up in a recent enforcement decision.

During an investigation by the Irish DPC, Meta unsuccessfully attempted to rely on the “explicit consent” derogation to justify its transfers of Facebook users’ personal data from Ireland to the US.

Here’s an extract from the Irish DPC’s decision, explaining why this approach would not work in Meta’s case.

Here’s the takeaway from this Meta decision:

- Each time you transfer someone’s personal data under the explicit consent derogation, you must:

- Obtain their explicit consent to that specific transfer

- Provide extensive information about the risks involved in that specific transfer

- All the other consent rules apply, including that the individual must be able to withdraw consent without detriment.

In Meta’s case, this would have been impractical, as users would be barraged with consent requests when using the platform. Therefore, the explicit consent derogation was not deemed appropriate.

Contract with the Data Subject

The “contract with the data subject” derogation covers a situation in which you need to transfer personal data in order to:

- Perform your obligations (or, if you are a processor, your controller’s obligations) under a contract with the data subject, or

- Implement pre-contractual measures taken at the request of the data subject (such as negotiating, providing information about, or entering into a contract).

As noted, this derogation is only for “occasional” use.

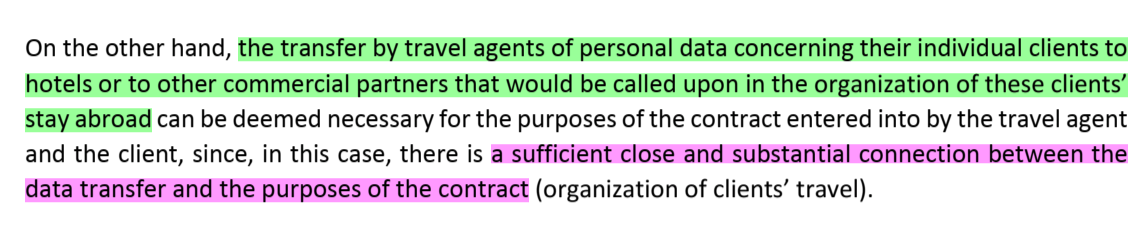

The EDPB provides three hypothetical examples of when the “contract with the data subject” derogation might apply.

Here’s the EDPB’s first example:

In this example, a travel agent needs to help organise its customers’ holiday. The travel agent transfers personal data to a hotel overseas using the “contract with the data subject” derogation.

Here are the EDPB’s second and third examples:

In these other examples:

- A company needs to transfer its sales manager’s personal data to clients overseas in order to arrange meetings.

- A bank needs to transfer its customer’s personal data to execute a payment.

Remember that these examples would not work if it was possible to put another data transfer safeguard in place, such as SCCs.

If you plan to use this derogation, you must tell people at the time you obtain their personal data, for example in your privacy notice, or whatever other document you use to meet your obligations under Article 13 or 14 of the GDPR.

Case Study: Google Analytics

Here’s another example of a company facing GDPR enforcement after relying on a derogation.

A German company was sanctioned by the North Rhine-Westphalia Consumer Center for transferring personal data to the US via Google Analytics. The company appealed the sanction at the Regional Court of Cologne.

The company had been relying on the legal basis of “contract” to collect personal data via Google Analytics, and the “contract with the data subject” derogation to transfer personal data to the US.

The court found the company could not rely on “contract” as its legal basis because the processing was not “necessary” for the performance of a contract. As such, the company could also not rely on the “contract with the data subject” derogation.

No Cookie Banners. Resilient against AdBlockers.

Try Wide Angle Analytics!

Contract Benefiting the Data Subject

The “contract benefitting the data subject” derogation covers a situation in which you need to transfer personal data in order to:

- Perform or conclude a contract that:

- Is between you (or, if you are a processor, your controller) and a person other than the data subject, and

- Is “in the interest” of the data subject.

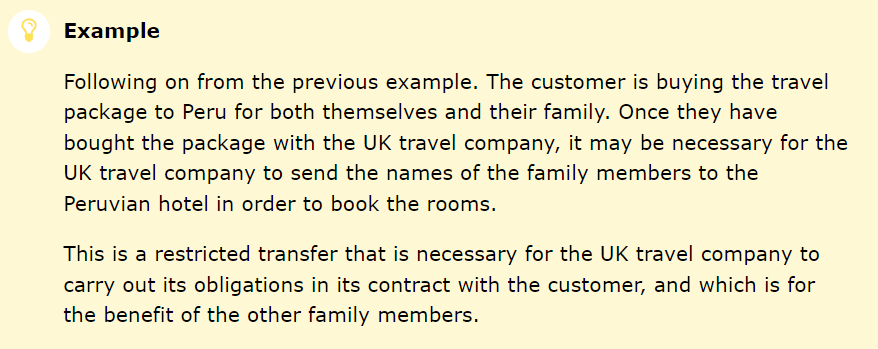

Here’s an example from the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO):

In this example, a customer buys a holiday in Peru from a travel agent. The travel agent must transfer the customer’s personal data to the hotel. The travel agent also needs to send personal data about the customer’s family members to the hotel.

Because there is no contract between the travel agent and other members of the customer’s family, the travel agent relies on the “contract benefitting the data subject” derogation to facilitate the transfer.

Public Interest

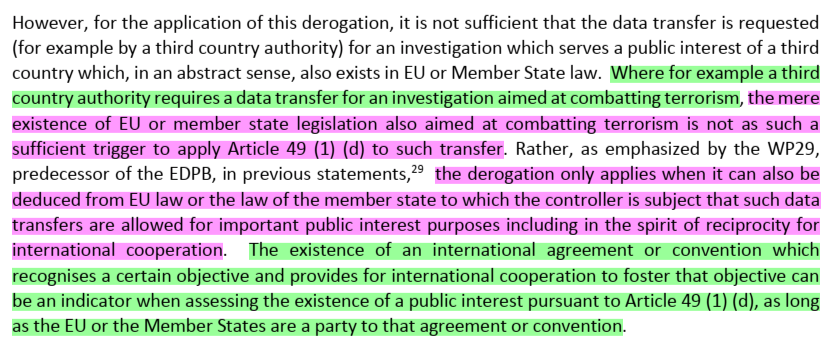

The “public interest” derogation applies if you need to transfer personal data for reasons of “important public interest”.

The important public interest must be recognised in a law that applies to the controller. Examples include transfers that form part of a criminal investigation, an exchange of information between tax authorities, or as part of a public health programme.

But, according to the following section of the EDPB’s guidance, the public interest derogation should be interpreted narrowly:

Let’s translate this guidance into an example scenario:

- A public authority in Russia contacts a French university.

- The Russian public authority requests personal data about a student suspected of terrorist acts.

- The request is valid under Russian law.

- France also has anti-terror laws.

The above points alone would not justify the transfer. The French university would need to assess whether the circumstances of transfer would justify using the derogation, including by reference to specific laws that apply to the university in this situation.

Legal Claims

The “legal claims” derogation applies if the transfer is “necessary for the establishment, exercise, or defense of legal claims”.

Recital 111 of the GDPR states that this derogation applies to a range of different types of processes, including:

- Judicial procedures

- Administrative procedures

- Any out-of-court procedure, including procedures before regulatory bodies.

The EDPB gives the example of administrative investigations in non-EEA countries, such as in the areas of “anti-trust law, corruption, insider trading, or similar situations”.

However, the EDPB also states:

“The derogation cannot be used to justify the transfer of personal data on the grounds of the mere possibility that legal proceedings or formal procedures may be brought in the future.”

Vital Interests

The “vital interests” derogation applies if the transfer is “necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject or of other persons, where the data subject is physically or legally incapable of giving consent”.

Protecting a person’s “vital interests” means protecting them from death or serious mental or physical harm.

Without a derogation like this, data protection law could lead to people dying or being badly hurt because controllers were unable to share personal data in an emergency.

Nonetheless, the EDPB provides a narrow interpretation of this derogation:

Here are some takeaways from this section of the EDPB guidance:

- The derogation covers physical and mental health issues.

- If the transfer covers health data, it must be necessary for an “essential diagnosis”.

- The person must be “physically or legally” incapable of giving consent. For example, if the person is unconscious, or lacks the capacity to consent due to serious mental health issues.

- If the person can consent, you must use the “explicit consent” derogation instead.

- The derogation cannot be used to justify general health research that might save lives in the future.

Public Register

The “public register” derogation covers transfers:

- Made from a register that is both:

- Intended to provide information to the public, according to EU or member state law, and

- Open to consultation, either by:

- The public in general, or

- Any person who can demonstrate a legitimate interest

- But only to the extent that the conditions laid down by EU or member state law for consultation are fulfilled in the particular case.

The UK’s ICO provides some examples of such registers, including “registers of companies, associations, land registers or public vehicle registers”.

Compelling Legitimate Interests

Finally, the “exception to the exceptions”: The “compelling legitimate interests” derogation.

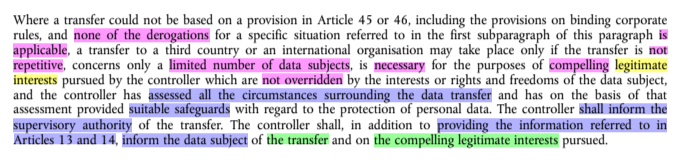

Here’s the derogation in full, at the second subparagraph of Article 49(1) of the GDPR:

Let’s break that down.

The “compelling legitimate interests” derogation must only be used where none of the other derogations applies.

The transfer must:

- Involve only a limited number of data subjects.

- Not be repetitive.

- Be necessary for the compelling, legitimate interests pursued by the controller.

As always, the controller’s interests must not be overridden by the data subjects’ rights and freedoms.

Before relying on the “compelling legitimate interests” derogation, you must:

- Assess all the circumstances of the transfer.

- Provide suitable safeguards to protect the personal data.

- Inform your data protection authority (DPA) that you intend to use the derogation.

- Provide the data subject with all the information required under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR.

- Inform the data subject about:

- The transfer, and

- The nature of your compelling legitimate interests.

Clearly, there is a lot of work to do before relying on this derogation.

The fact that the controller’s legitimate interests must be “compelling” means that this is a higher threshold than the usual “legitimate interests” legal basis under Article 6 (1) (f) of the GDPR. Read our guidance on “legitimate interests” to learn more.

The EDPB provides one example of where this derogation might apply:

If a data controller is compelled to transfer the personal data in order to protect its organisation or systems from serious immediate harm or from a severe penalty which would seriously affect its business.

Remember, though, that such a transfer would only be legal under this derogation if none of the usual international transfer mechanisms (such as SCCs) or derogations (such as “explict consent”) apply.

Four Basic Principles for the GDPR’s International Transfer Derogations

Here are four basic principles that apply to the GDPR’s international transfer derogations.

- The derogations are a “last resort” and for exceptional use only.

- There are important conditions and requirements that apply to each derogation. You must implement these before using a derogation.

- You don’t normally need to put data transfer safeguards in place when relying on a derogation (unless you’re relying on the “compelling legitimate interests” derogation).

- Although the derogations allow for an exception to the GDPR’s international data transfer rules, all of the GDPR’s other rules and principles still apply.

No Cookie Banners. Resilient against AdBlockers.

Try Wide Angle Analytics!