Data Protection and Privacy in 2023: Main Themes

Here are the main issues that kept data protection and privacy fans awake at night in 2023.

Consent or pay: Is it legal under the GDPR?

Despite passing in 2016, some parts of the GDPR remain open to debate. One of the most hotly-contested GDPR issues in 2023 was whether the law allows for so-called “consent or pay” policies.

In September, Meta announced plans to offer European Economic Area (EEA)-based Facebook and Instagram users three options:

- Agree to behavioural advertising (tracking),

- Pay around €10 per month for a “tracking-free” version of Facebook or Instagram, or

- Leave Facebook and Instagram.

So why is Meta doing this? And is it legal? Let’s go back to the very first days of 2023.

January: Meta switches from contract to legitimate interests

In January 2023, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) forced the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) to order Meta not to rely on “contract” for behavioural advertising.

Meta’s terms of service included a clause requiring the user to accept behavioural ads as a condition for using the platform. According to the EDPB, ad-targeting was not “necessary” for Meta to deliver its services, so the company had to find a new legal basis.

A few weeks later, Meta switched to “legitimate interests”, allowing Facebook and Instagram users across the EEA to opt out of behavioural ads if they filled out a (long) form explaining why their rights were more important than Meta’s business model.

Was “legitimate interests” the right choice of legal basis for Meta’s ad-targeting? Decide for yourself by reading What is Legitimate Interests Under the GDPR?

July: Norway condemns Meta’s new legal basis

In the summer, the Norweigan DPA issued an emergency order requiring Meta to stop delivering behavioural ads to users in Norway without consent. The order included a threat of daily fines, up to around €87,000 per day, and a deadline of 4 August.

Meta did not comply with the Norwegian order. However, due to the upcoming enforcement of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and a loss against the Austrian competition authority at the CJEU, the company later announced that it planned to switch to “consent” for behavioural ads.

But the Norwegian regulator was sceptical about how Meta’s consent process would look.

September: Meta switches to ‘Consent or Pay

In the CJEU case against the Austrian competition regulator mentioned above, the court found that Meta needed consent for behavioural ads.

But one short passage from the judgment gave the company some wriggle room.

The CJEU said, in passing, that Meta must provide a tracking-free option for users who refuse consent—for “an appropriate fee” if “necessary”.

So, is “consent or pay” legal under the GDPR?

- Is “freely given” consent possible if refusing consent incurs a fee?

- Do you incur a “detriment” if you refuse consent?

- And if you consent to tracking, then change your mind, you’ll have to pay a monthly fee. Does this meet the GDPR’s requirement that it must be “as easy to withdraw as to give consent”?

In early 2024, we should hear what the EDPB and the Irish DPC say about this debate. Max Schrems’ campaign group, noyb, has also submitted two complaints about the policy to the Austrian DPA.

But don’t expect Meta to change course any time soon.

Want to get consent right under the GDPR? Read our collection: Everything You Need to Know About GDPR Consent.

Artificial intelligence: Regulators begin to find their feet

In the final quarter of 2022, AI hit the mainstream—thanks to applications like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and image-generator Midjourney.

And in 2023, DPAs and legislators got serious about regulating the technology.

EU institutions negotiated the AI Act with renewed vigour and reached a deal before the year was out. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) brought enforcement action against a retailer using facial recognition.

We’ll look at those developments later in the article. For now, let’s examine the first high-profile battle between the GDPR and generative AI.

March: Italy vs ChatGPT

At the end of March, the Italian DPA, known as the “Garante”, temporarily banned OpenAI from processing personal data about people in Italy via ChatGPT.

“We obviously defer to the Italian government and have ceased offering ChatGPT in Italy,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said on Twitter. “Though we think we are following all privacy laws,” he added.

There are a few issues with this tweet:

- The Garante is not the Italian government.

- The GDPR is technically not a privacy law, but a data protection law.

- The Garante didn’t actually order OpenAI to stop offering ChatGPT in Italy. The order was to stop processing personal data about people in Italy.

To be fair, complying with the order would likely have been impossible without shutting off access to the chatbot.

So, OpenAI pulled out of Italy while it tried to address the Italian DPA’s issues.

April: OpenAI placates the Garante

The Garante raised many GDPR issues with ChatGPT, including:

- The alleged lack of a legal basis for using personal data for training purposes,

- Inaccurate personal data appearing in outputs,

- A lack of transparency,

- No age verification system to prevent children from using the platform.

Despite these issues, the Garante lifted its ban by the end of April after OpenAI made some improvements to its data protection compliance programme.

The episode might have reassured certain companies that generative AI is compatible with the GDPR—despite the colossal amounts of personal data required to train such systems.

But it seems the Garante wasn’t completely satisfied with OpenAI’s compliance efforts.

January 2024: Garante re-opens its case against OpenAI

This January, the Garante announced that it was investigating OpenAI again.

The regulator did not specify why it had reopened OpenAI’s case, but the tricky issue of age verification was left on the table last year.

Age-gating online services is no easy task—particularly in light of the GDPR’s “data minimisation” principle.

But the age verification problem affects many companies. If the Garante has taken issue with how OpenAI trains its Large Language Model, this could present a fundamental and irreconcilable issue for AI companies operating in the EU.

The United States: Have meaningful privacy protections finally arrived?

The US has long been considered a privacy “Wild West”. Until recently, only specific sectors—like healthcare, banking, and certain federal government bodies—faced any significant privacy regulation.

That’s changing fast. In 2023, five state privacy laws took effect, and many more passed. These new, “comprehensive” privacy laws are not as strict or as broad as data protection laws across Europe, Latin America, or Africa—but thousands of businesses will need to meet their requirements.

California gives way to Virginia

Back in 2003, California passed a very modest privacy law called the California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA).

CalOPPA only requires businesses to publish a short privacy policy. But the law applies to every company collecting certain types of personal information online from California residents—and so it made a mark on the World Wide Web.

In 2018, California became the first state to pass a serious privacy law—the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). Despite its somewhat cumbersome drafting and relatively narrow application, the law forced many US businesses to consider privacy for the first time.

On New Year’s Day 2023, the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) amended the CCPA, bringing California residents new rights to opt out of targeted advertising and to limit how businesses use their sensitive data. The CPRA also established the first dedicated US privacy regulator, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA).

But America’s second comprehensive privacy law—the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA), which also took effect in January 2023—looked very different from California’s, in part thanks to the lobbying efforts of Amazon and other big tech firms.

The rise of Virginia-style laws

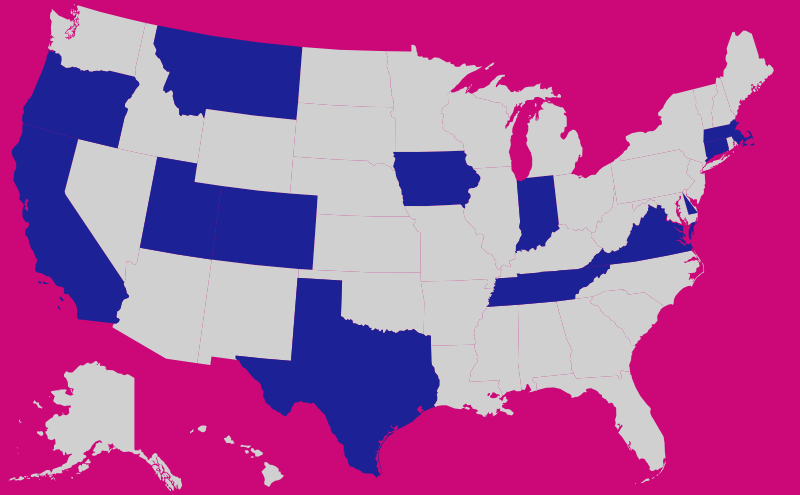

In 2023, comprehensive privacy laws either passed or took effect in the following 12 US states:

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Massachusetts

- Montana

- Oregon

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

Besides California, all these states used Virginia’s VCDPA as a template for their own privacy laws.

Some states, such as Iowa, Tennessee, and Utah, passed a weaker version, narrowing the scope or removing certain privacy rights. But perhaps surprisingly, most states went further than Virginia.

In seven of the above states, businesses will need to respect signals sent by “universal opt-out mechanisms”—browser features or extensions such as the Global Privacy Control (GPC) that tell businesses not to sell the user’s personal data or target them with behavioural ads.

Note: A German court recently found that controllers under the GDPR must take account of a very early universal opt-out mechanism: Do Not Track (DNT). Read our article: Is Recognising Do Not Track (DNT) Signals Required Under the GDPR?

But things are getting complicated with so many similar laws containing small but important differences. And there is plenty more legislation to figure out besides these twelve laws.

A puzzling patchwork

Unless the US passes a federal privacy law (and don’t assume that it will), some businesses will struggle to comply with the multitude of privacy laws that apply to them.

In addition to the 12 states with comprehensive privacy laws, several states passed sector-specific privacy laws last year.

- Washington’s My Health My Data Act (MHMDA), which passed in April, is a very strict health privacy law with a deceptively broad application and a private right of action. Nevada also passed a narrower copycat version of the law.

- Florida’s Digital Bill of Rights, passed in May, applies only to billion-dollar businesses providing a narrow range of services (despite its rather grandiose name).

- Connecticut’s SB 3, passed in June, amending the state’s already relatively strict privacy law and bringing new rules to companies collecting health data or offering online services to kids.

State legislatures are debating dozens of further privacy laws across the US—and two new comprehensive privacy laws passed within the first three weeks of 2024 (in New Jersey and New Hampshire).

Now add the FTC’s enforcement rampage (which hit Amazon, Microsoft, and many other companies last year), proposed amendments to federal children’s privacy law, and new privacy regulations adopted by state authorities in California and Colorado.

2023 was the year that US privacy law became more complex—and arguably more interesting—than the EU’s.