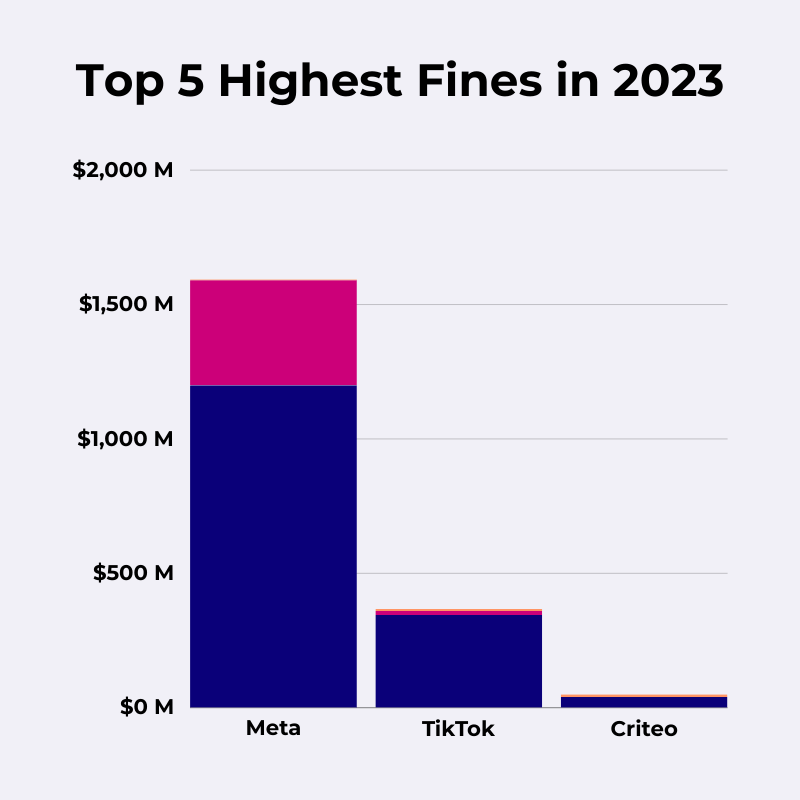

The 5 Highest GDPR Fines of 2023

According to CMS, nearly 500 GDPR fines were issued in 2023. Here’s a look at the five highest data protection penalties (spoiler alert: Four of the fines belong to the same two companies).

Meta: €1.2 billion

- Meta

- 22 May 2023

- Ireland

- Article 46 (1) GDPR

- €1.2 billion fine and corrective measures

2023 saw the largest GDPR fine yet—by some distance—as the effects of 2020’s Schrems II case continued to play out.

Meta got its €1.2 billion fine from the Irish DPC last May, and it’s nearly half a billion euros higher than the previous record-holder—Amazon, whose €746 million fine from 2021 remains under appeal.

Meta’s fine related to international data transfers.

In the Irish case that became Schrems II, Meta was ordered to ensure its EEA-based Facebook users’ rights were not being violated by transfers of personal data from Meta Platforms Ireland to Meta Platforms Inc. (based in California).

Meta continued its transfers, relying on Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs)—despite the CJEU’s finding that SCCs do not (in themselves) protect the “fundamental rights and freedoms” of people in the EU.

The penalty was exceptionally high because the company was found to have defied the court’s ruling for nearly three years following the case. DPAs in Austria, Denmark, France, and Spain successfully argued that imposing a fine that was too small risked endangering people’s fundamental rights.

But payout aside, the Irish DPC’s orders against Meta were particularly significant. The regulator ordered Meta to:

- Suspend all transfers of personal data to the US within five months, and

- Stop the unlawful processing of personal data in the US, including data storage, within six months.

Had Meta implemented these changes, it is unlikely that the company would have been able to continue operations in the EEA.

But Meta’s European operations were rescued—perhaps temporarily—by the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF), which we’ll look at below.

Key takeaway: Before relying on one of the international data transfer mechanisms at Article 46 GDPR, a controller or processor must ensure that the transfer will not risk violating data subjects’ fundamental rights and freedoms. See our article Standard Contractual Clauses: The Definitive Guide.

Meta: €390 million

- Meta

- 4 January 2023

- Article 5 (1) (a), (c) GDPR, Article 6 (1) GDPR, Article 12 (1) GDPR, Article. 24 GDPR, Article 25 (1), (2) GDPR, Article 35 GDPR

- Ireland

- €390 million and corrective measures

The second-highest GDPR fine of 2023, and the fourth-highest of all time, was also issued to Meta. The Irish DPC’s €390 million fine concerned a whole range of GDPR violations, but the focus was on Meta’s legal basis for delivering behavioural ads.

(In fact, this is technically two separate fines— a €210 million fine for violations related to Facebook and a €180 million fine concerning Instagram. But Meta is “the controller”, so it’s reasonable to combine the two penalties.)

As explained in the “consent or pay” section above, the Irish DPC ordered Meta to stop relying on “contract” to deliver behavioural ads in January. As usual, Ireland was reluctant to deliver the order and was forced to do so after a “binding decision” by the EDPB.

But the story starts before the GDPR even took effect.

Under the Data Protection Directive, Meta had relied on a form of “assumed consent”. The company feared this policy would not meet the GDPR’s stricter standards. Meta consulted the Irish DPC, and—on the day the GDPR took effect—started relying on “contract”.

As shown in draft EDPB documents leaked by noyb in 2021, the Irish DPC advocated for allowing controllers to rely on “contract” for behavioural advertising—a position described by fellow regulators as “undermining the system and spirit of the GDPR” and “contrary to everything we believe in".

The Irish DPC and Meta both argued that data protection regulators do not have the power to judge the validity of contracts (in this case, Meta’s terms of service agreement, which is accepted by each Facebook and Instagram user).

Both parties agreed that behavioural advertising was “necessary for the performance of a contract” because behavioural ads are a “core part” of Meta’s services—and because Meta’s business model depends on ad revenues.

The EDPB disagreed, finding that this concept of “necessity” would significantly weaken the GDPR’s protections. Meta was ordered to find a new legal basis—and since then, the company has switched legal basis twice.

Key takeaway: Processing personal data is only “necessary” for the performance of a contract if the controller cannot deliver its core services without processing personal data—not merely because the processing funds its general business operations. For more information on the GDPR’s legal bases, see our article What Is Consent Under the GDPR?

TikTok: €345 million

- TikTok

- 1 September, 2023

- Article 5 (1) (c), (f) GDPR, Article 12 (1) GDPR, Article 13 (1) (e) GDPR, Article 24 (1) GDPR, Article 25 (1), (2) GDPR

- Ireland

- €345 million

Last year’s third-highest fine was against TikTok. The penalty was issued—again—by the Irish DPC and—again—after some arm-twisting by the EDPB.

The Irish DPC made the following findings, most of which had been corrected by TikTok several years prior to the decision:

- TikTok enabled any user to view children’s TikTok profiles and content. The option for children to make their profiles public was “off” by default, violating the GDPR’s obligations around “data protection by design and by default”.

- TikTok failed to consider and mitigate the risks of children's content being made public to a “potentially unlimited number of people".

- TikTok’s “Family Pairing” feature, intended to allow parents to link their account to their kid's account, enabled any user to “pair” with any child over 16. This meant adults could send children direct messages.

- TikTok’s privacy information was not sufficiently clear and did not warn people that their personal data might be made public.

- TikTok violated the "fairness" principle by nudging users towards weaker privacy settings during account setup.

The DPC did not want to make this final “fairness” finding—but was forced to do so following another EDPB "binding decision". The German DPA explicitly mentioned TikTok’s alleged use of “dark patterns” as the reason for this finding.

Key takeaway: “Dark patterns”—manipulative design features that attempt to influence a user’s choice of privacy settings—violate the “fairness” element of the GDPR’s principle of “lawfulness, fairness, and transparency”. See our article Dark Patterns: 10 Examples of Manipulative Consent Requests.

Criteo: €40 million

- Criteo

- 15 June 2023

- Article 7 (1), (3) GDPR, Article 12 GDPR, Article 13 GDPR, Article 15 (1) GDPR, Article 17 (1) GDPR, Article 26 GDPR

- France

- €40 million and corrective measures

The French DPA delivered the largest fine ever issued to a European company last June, hitting French adtech firm Criteo with a €40 million penalty over its “behavioural retargeting” services.

Criteo relied on people’s consent to process their personal data and target them with ads. The personal data was collected via cookies.

But even though Criteo’s advertising partners—rather than Criteo itself—were responsible for obtaining consent, the French DPA found Criteo had violated Article 7 (1) of the GDPR, which requires the controller to demonstrate the data subject has given consent.

In addition to being unable to demonstrate consent, the French DPA found that Criteo had:

- Failed to uphold people’s rights of access and erasure,

- Published a vague and non-transparent privacy notice, and

- Failed to enter into a suitable “joint controller” agreement with its partners.

Key takeaway: If you’re relying on consent, make sure you can demonstrate consent. See our article on How to Record Consent Under GDPR for more about how to do this.

TikTok €14.5 million

- TikTok

- 4 April 2023

- Article 5 (1) (a) UK GDPR, Article 8 UK GDPR, Article 12 UK GDPR, Article 13 UK GDPR

- United Kingdom

- €14.5 million and corrective measures

2023’s fifth-highest fine was technically issued under the “UK GDPR” rather than the GDPR—but the UK’s data protection law remains substantively identical to that of the EU (for now).

The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) initially threatened a fine of more than double the eventual €14.5 million amount—and also dropped allegations that the company had violated the rules on “special category data” under Article 9.

(Author’s note: I asked the ICO for information about why it did not pursue its Article 9 allegations, but the regulator rejected my request—partly on the grounds that it would enable other organisations to evade the ICO’s “law enforcement functions”.)

The main issue for TikTok is related to Article 8 UK GDPR, which requires certain online services relying on “consent” to process a child’s personal data to obtain consent from the child’s parents.

But there’s a complication: TikTok only relies on “consent” for behavioural advertising—and, for whatever reason, the ICO’s investigation did not cover this activity.

For the processing investigated by the ICO, which mostly related to delivering content and maintaining users’ accounts, TikTok relied on “contract”, even for users under 13 years old. The ICO found that young children cannot agree to contracts, and so TikTok should have sought parental consent instead.

Besides this (arguably somewhat muddled) legal basis finding, the ICO also criticised TikTok’s privacy notices and ordered the company to establish effective age verification methods to keep younger children off of its platform.

Key takeaway: If young children use your services, or you suspect young children are using your services, consider whether you should be obtaining consent from their parents—and make sure your privacy notices are easy for a child to understand.